I just wrote about five paragraphs of brilliant thoughts and then, inadvertantly, opened another web page on top of it without hitting the + sign and lost all of it. DOH! It is not the first time I’ve done this bone-headed maneuver and won’t be the last.

Three people saying “GO” is sufficient for me to continue. This site is a bit annoying for two reasons, 1) it does not use the OS spell checker which I need, and 2) has an archaic image adding system where all the images must be uploaded to an image site and then downloaded here. I post on many sites and this one is the most awkward. Be that as it may, it’s an important site with many participants so it is worth the effort.

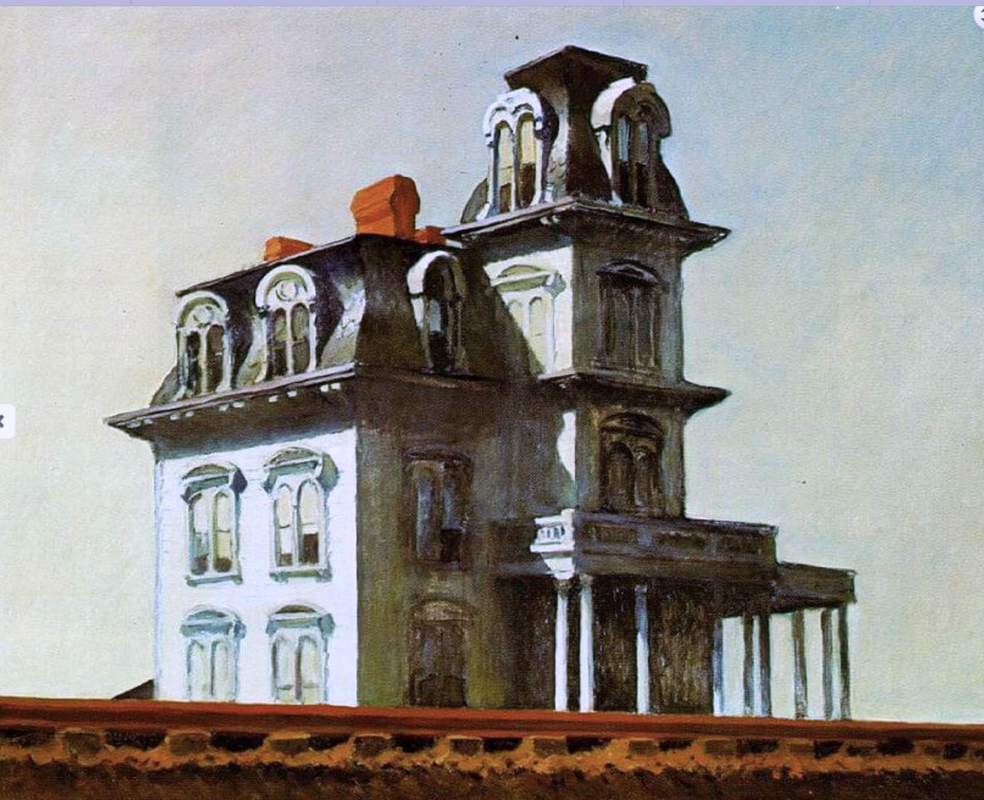

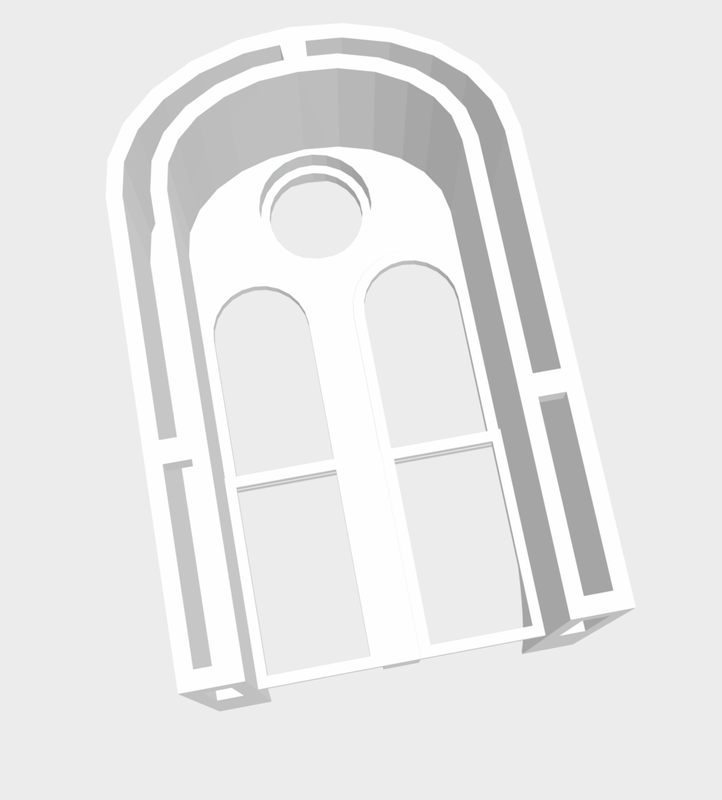

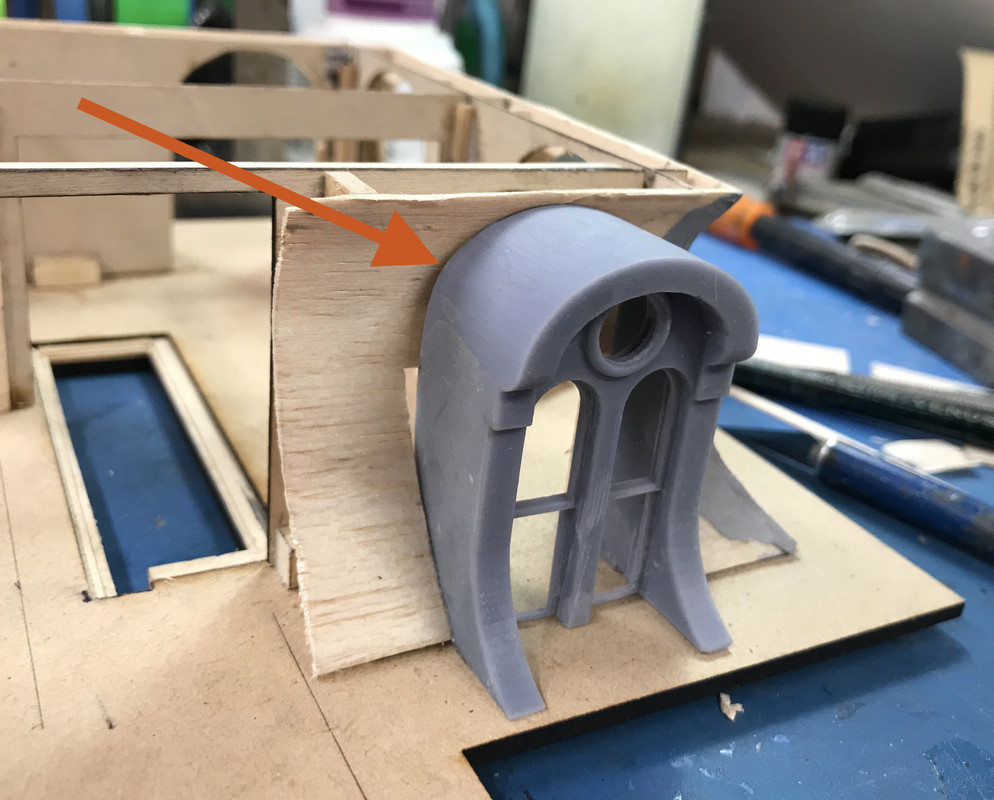

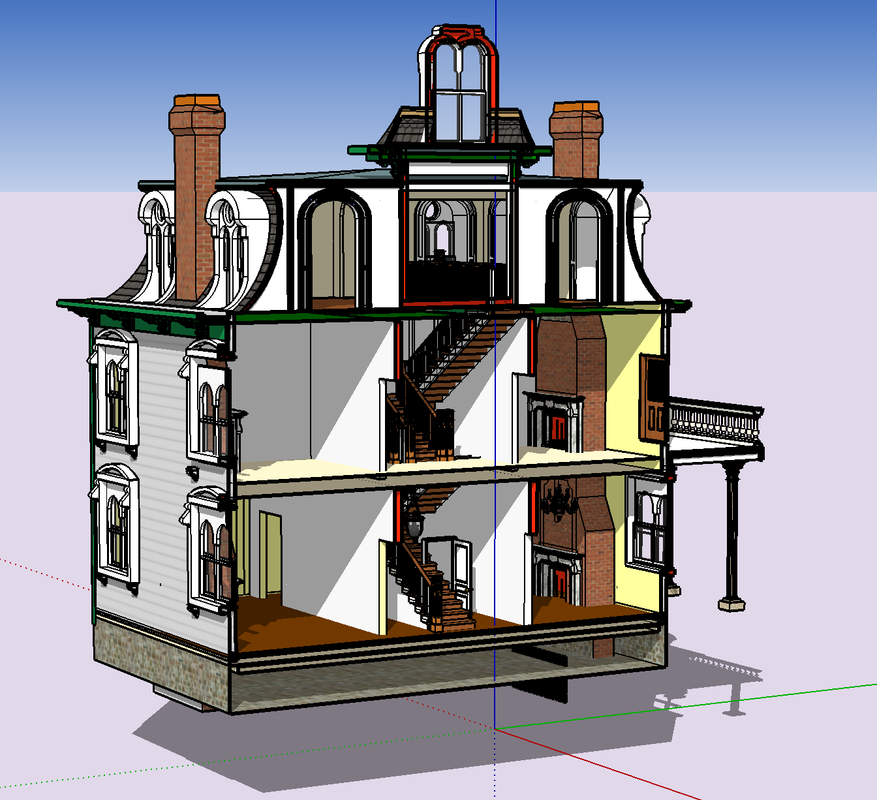

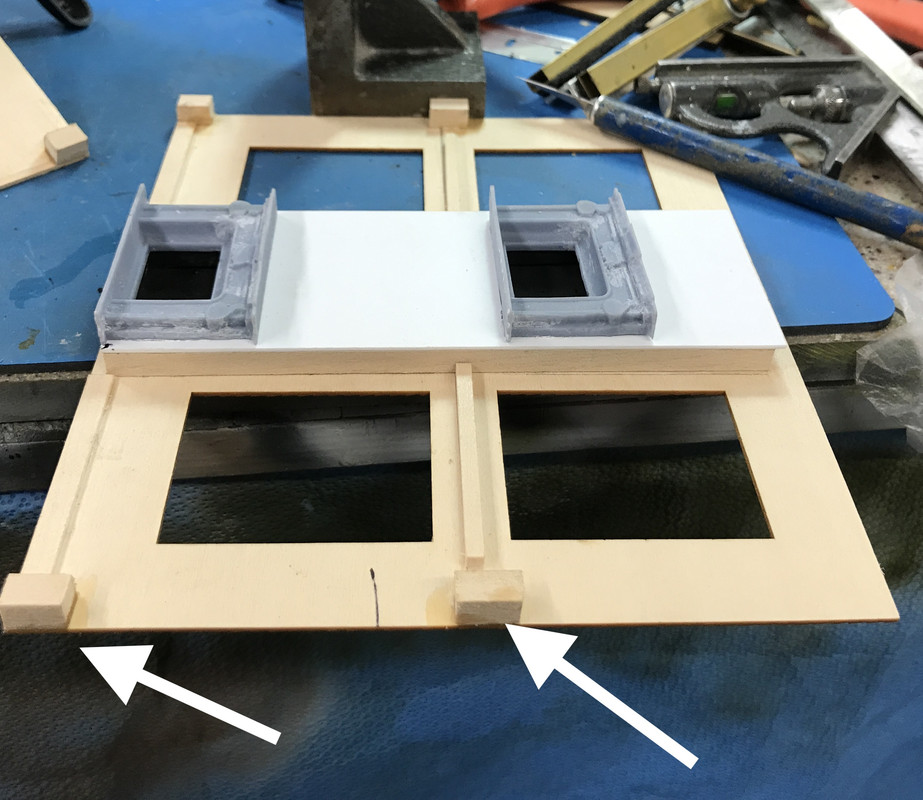

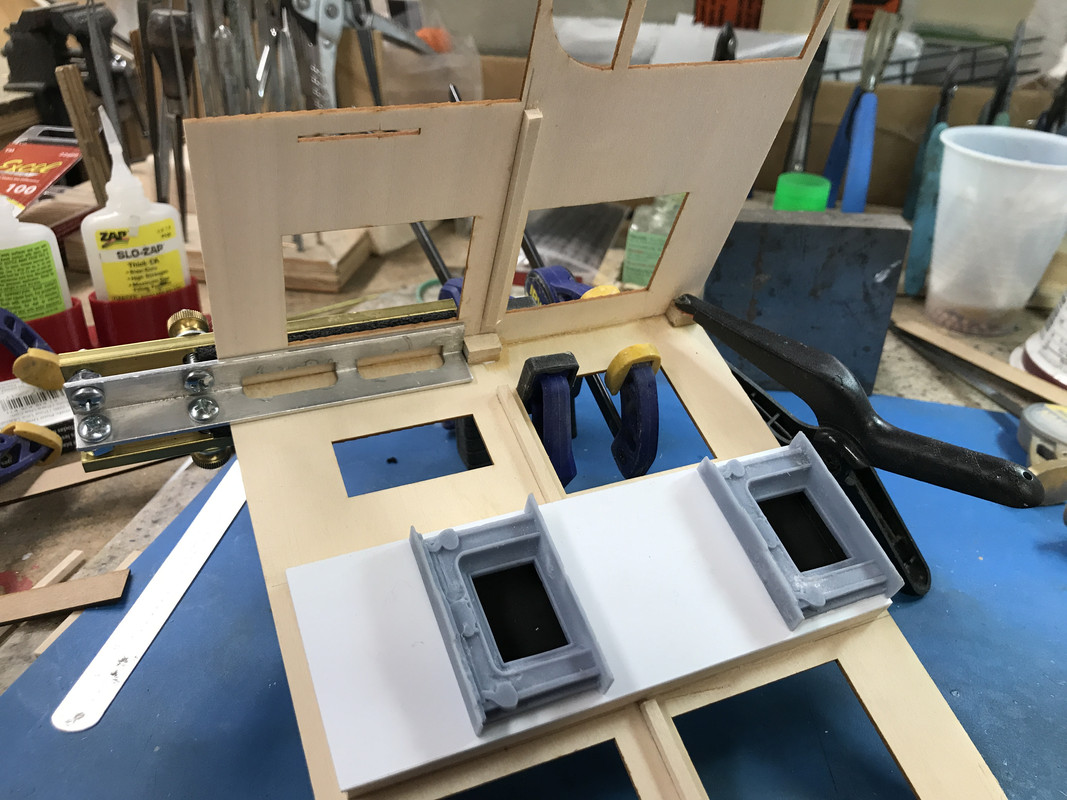

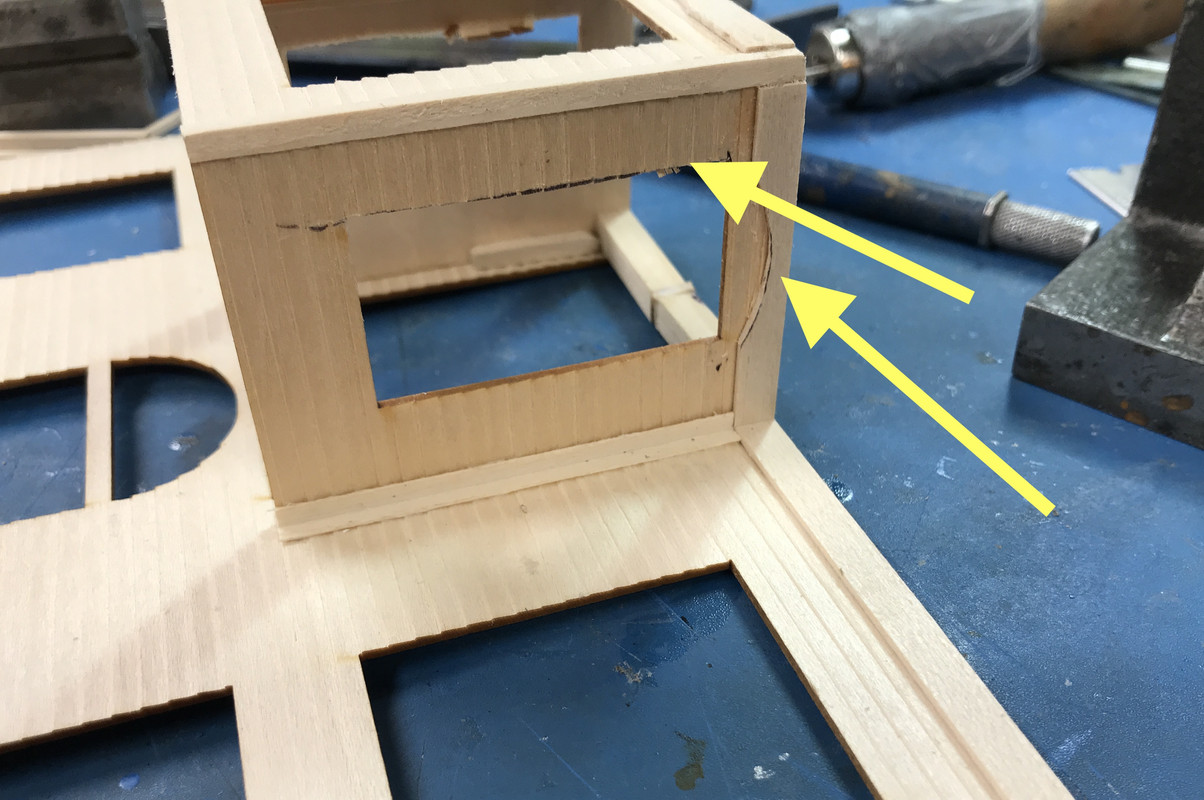

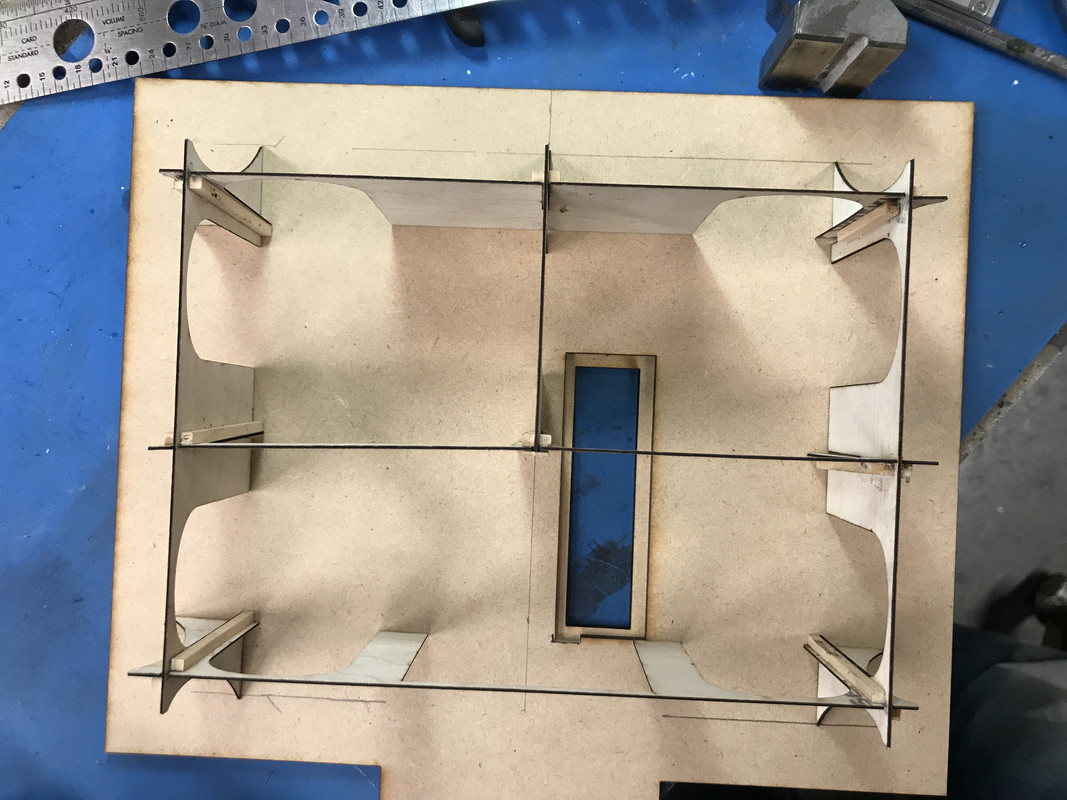

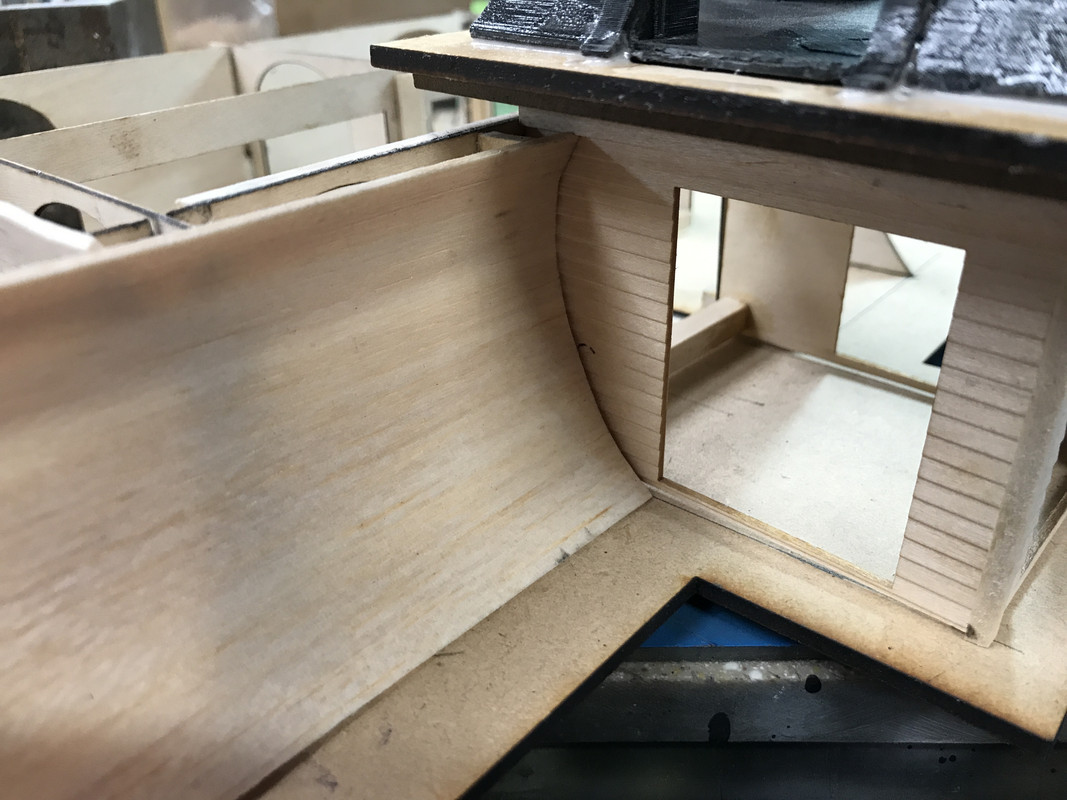

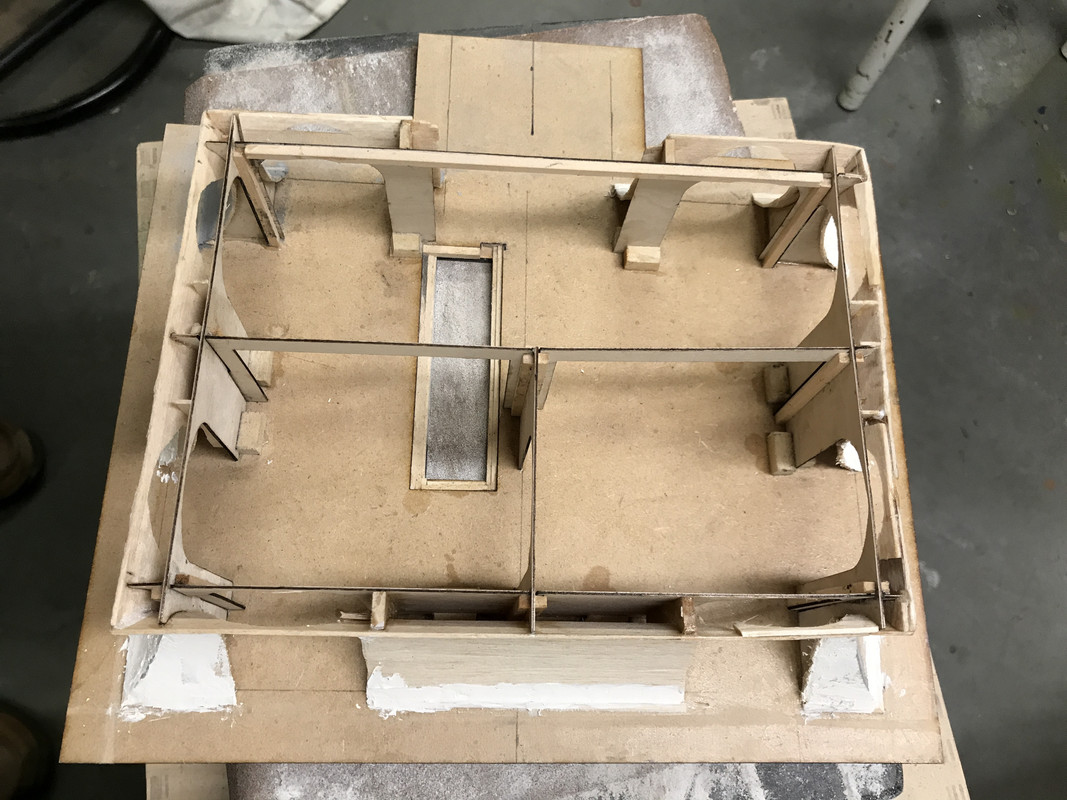

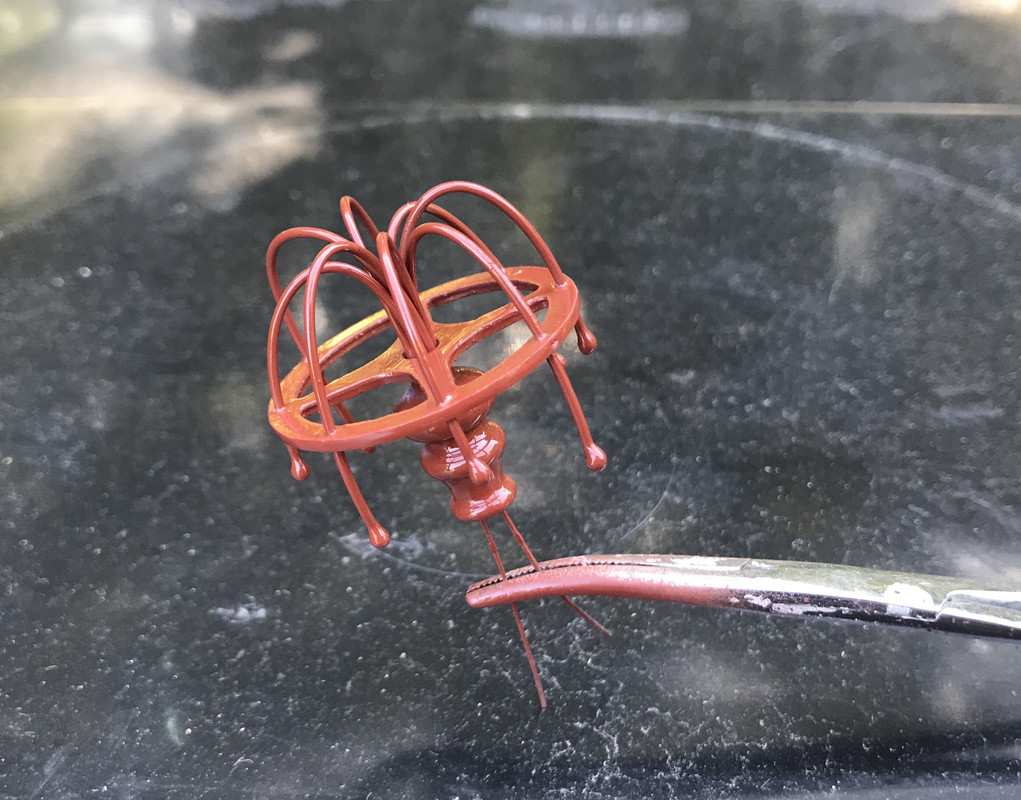

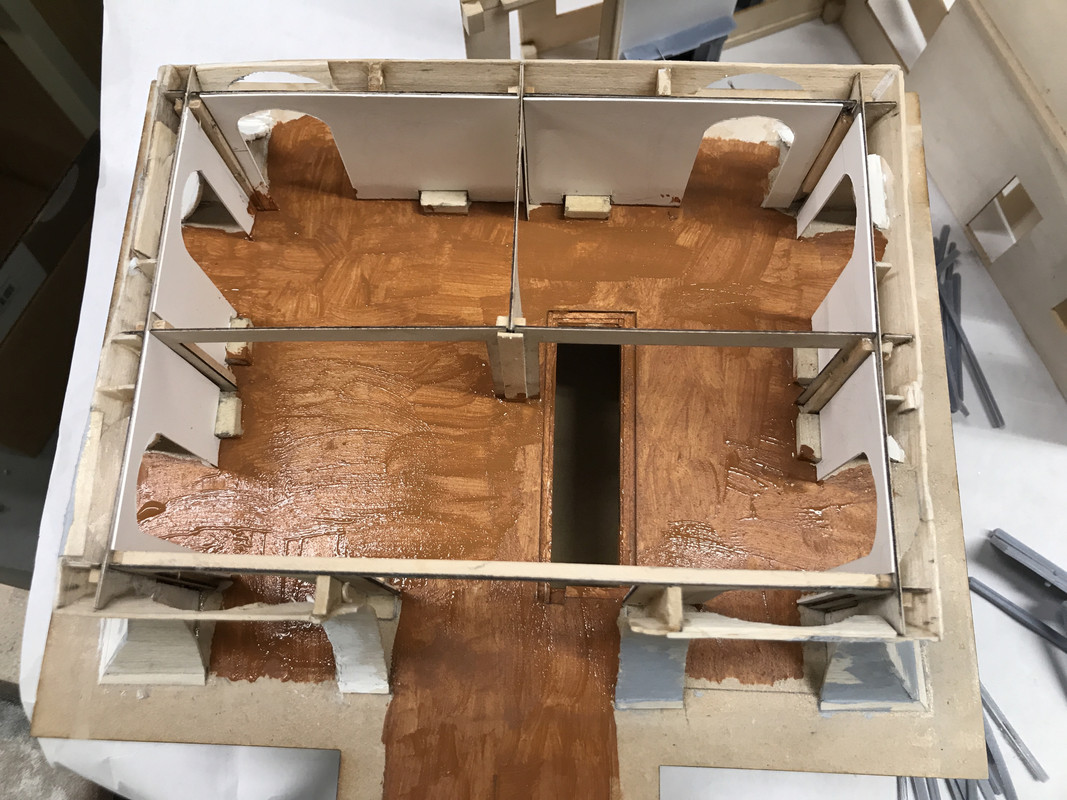

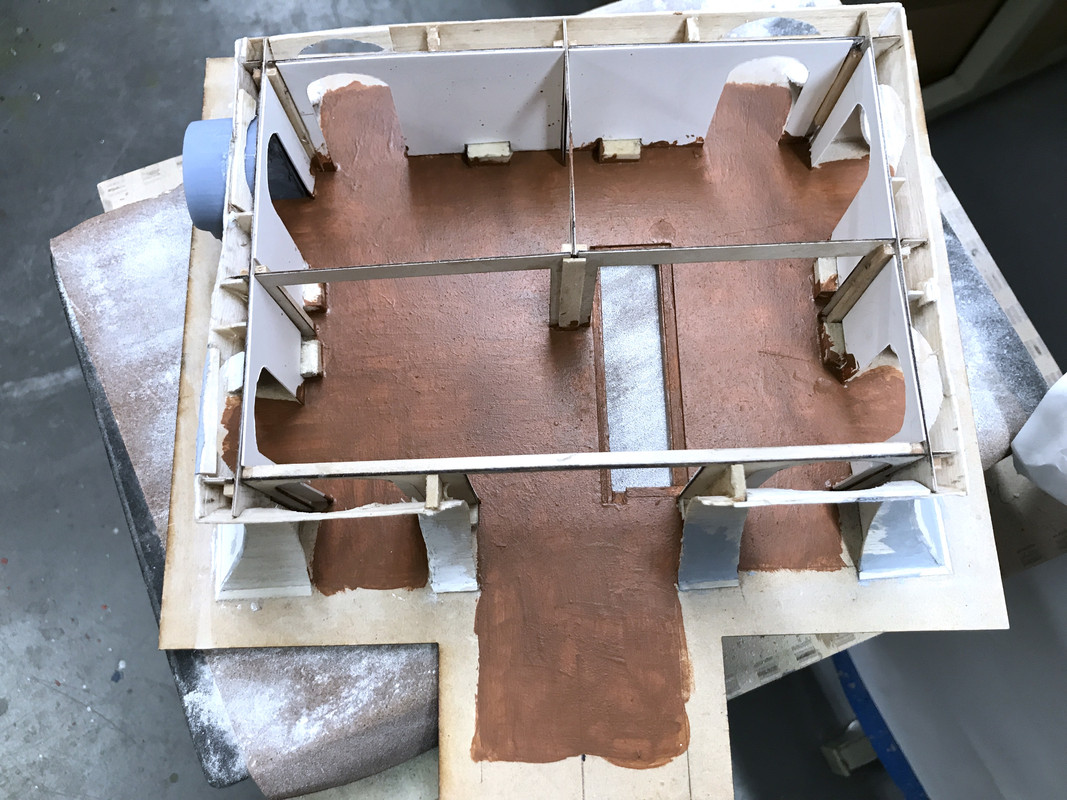

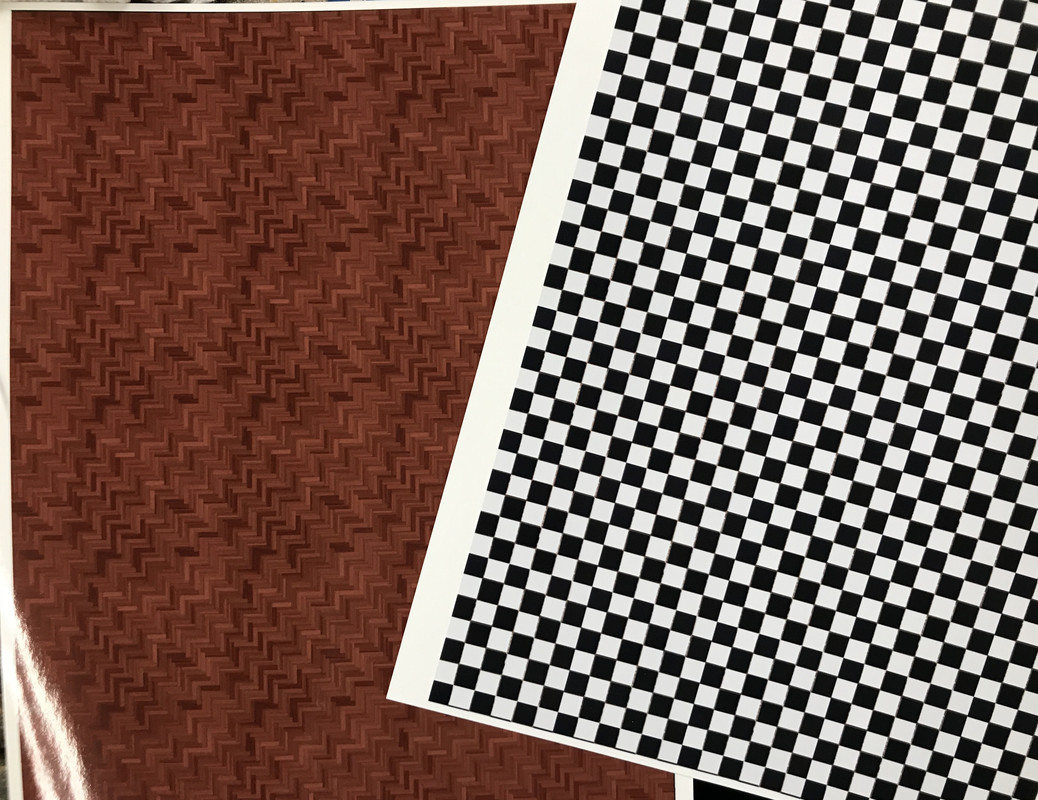

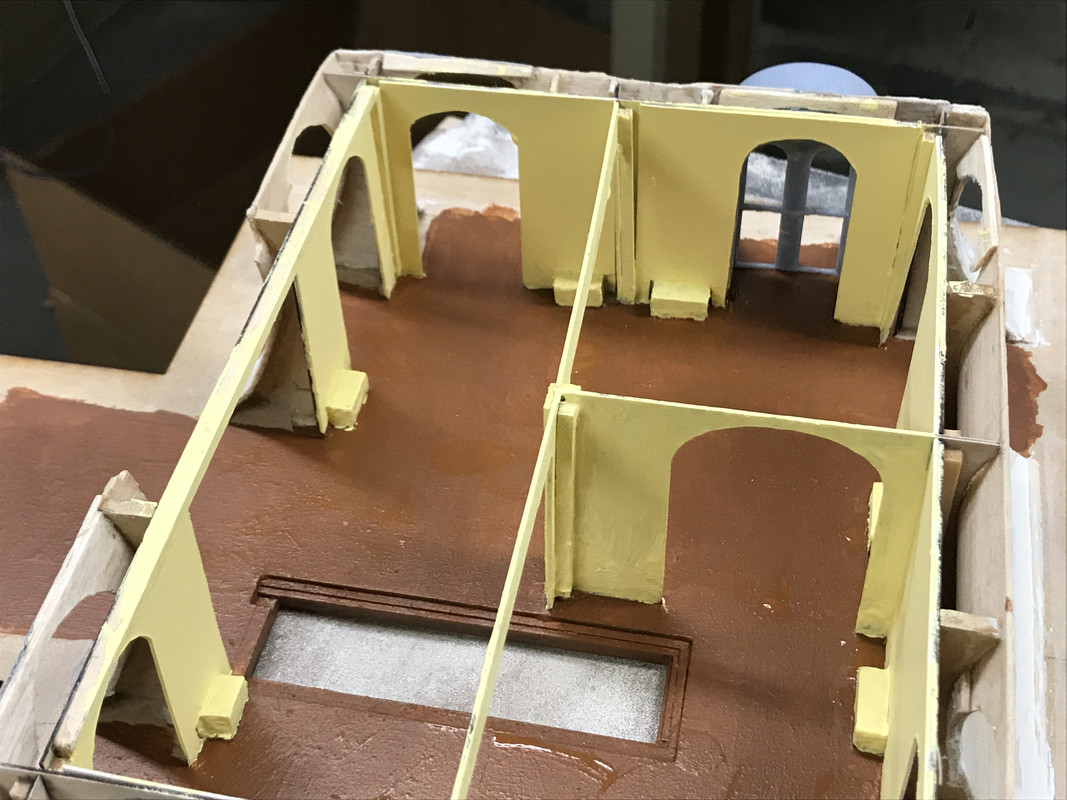

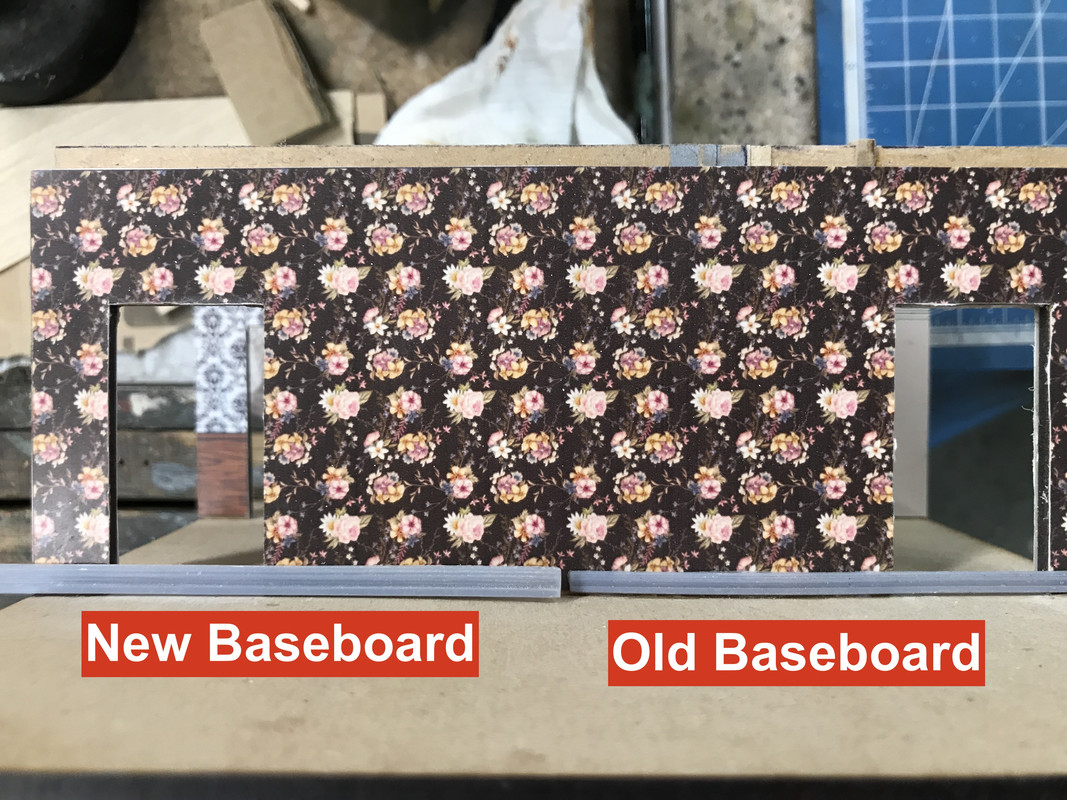

As I said, I would take y’all back to the beginning and tell the whole story. This project is as much a drawing challenge as it is a model building one. Once I decided on building another Hopper painting and chose this one, what I was presented with was a series of drawing challenges. One of the most essential were those characteristic Mansard windows. They make the building and if I couldn’t draw them, I couldn’t print them. And if I couldn’t print them, there would be no model.

What follows is a lot of information about 3D Printing. If you’re already up-to-speed or not interested, you can skip down to the bottom. I think it’s germane to this project as a whole, since so much has been created on the printer and more time was spent producing those parts than building the structure itself. 3D printing has changed the modeler’s question from “How do I build that?” to “How do I draw that?”. If I can draw it, I can make it.

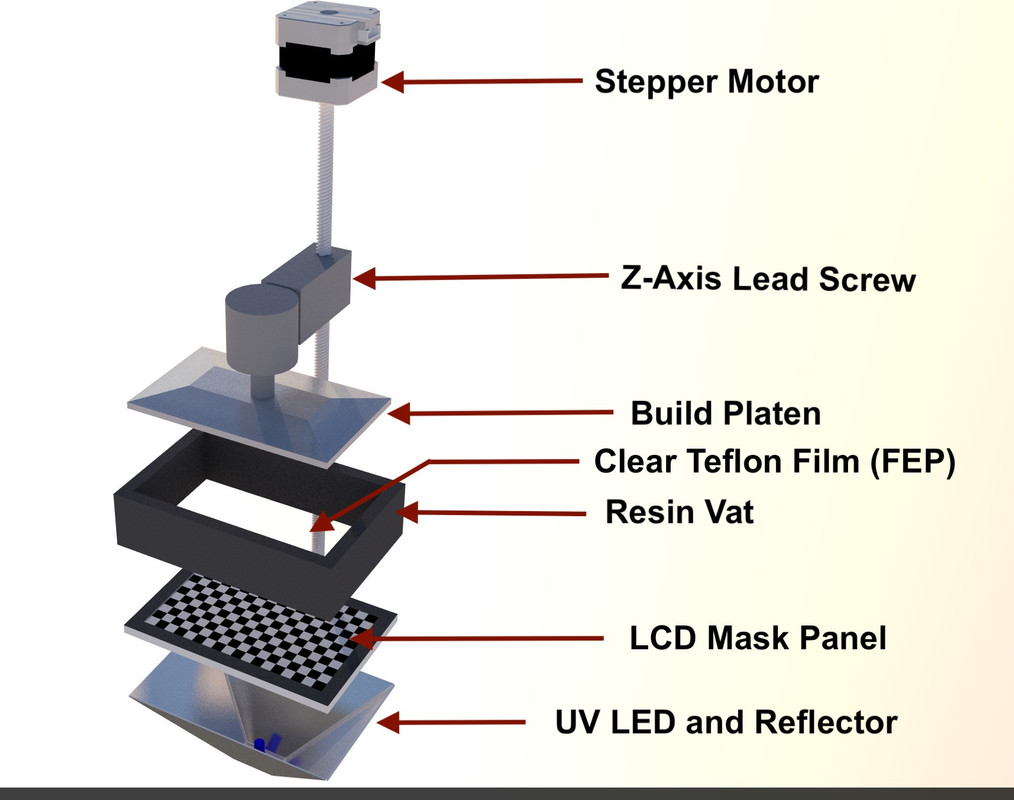

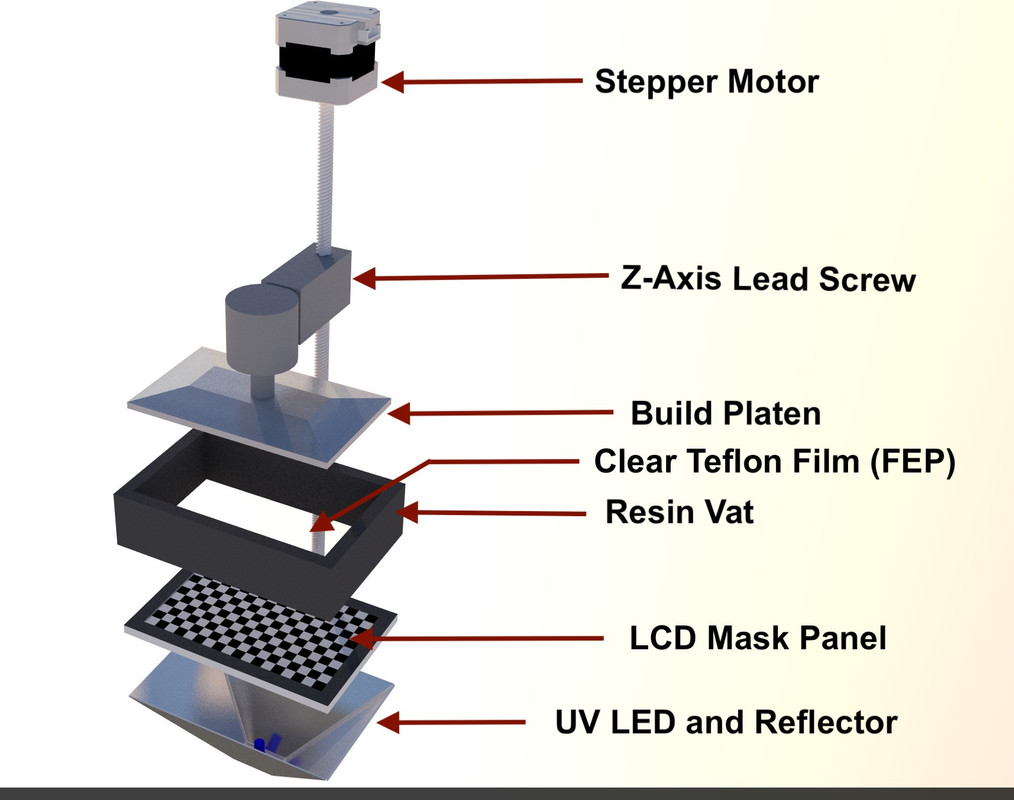

I’ve been 3D printing since June of '19, when the price of high resolution resin printers dropped from over $3,000 to $350 or less (much less). The reason for this precipitous drop was the mergining of the cell phone LCD screen and some UV LEDs to the resin printing process. Up to that point, resin printers employed either lasers to draw the object in the UV curable resin (very expensive) or DLP video projection to create the layer images in the resin (just plain expensive). Then along comes some innovators who created the layer images on the LCD screen and illuminated it with the UV LEDs and Volia! a printer basically cobbled together with off-the-shelf parts that are produced by the millions. The price dropped, but the resoution did not. My little $350 Elegoo Mars printer can produce parts down to a layer thickness of 10 microns. That’s a layer that’s 0.00075" or four times finer than a human hair. I generally produce parts with layer thickness of 40 to 50 microns.

The orange cover blocks ambient UV light from curing the resin in the vat at the bottom. Elegoo has just come out with the “Saturn” model which is about 2.5X the volume of the Mars. The resolution of the Mars is actually a bit better. Besides the vertical resolution which is controlled by how fine the Z-Axis stepper motor can control, the lateral resolution is a result of the pixel density of the LCD screen. The Mars has a 2k screen which gives a pretty fine horizontal resolution. The Saturn uses a 4K UHD screen, but it is 2.5X the area, so the actual resolution is a slight bit less.

You may be familiar with the more common Filament Deposition Printers (FDM) which I call “String Printers”. FDM machines work by melting a polymer and extruding a thin string of molten polymer into a pattern driven by X-Y-Z stepper motors. It resembles the process used when decorating a cake. These are seen at all the Maker Fairs and almost every school has them now. FDM machines have their place, but it’s not producing parts in our model making scales of 1/32 and smaller. As each layer of string is deposited there are visible lines like a tiny log cabin being built. For 1:1 parts, FDMs are quite useful. FDM machines’ lower limit is about 50 microns, but they’re very temperamental at that resolution. Generally they print layer thickness over 100 microns (1/10th of a mm). At that resolution in 1:48 you have visible layer lines that need fixing.

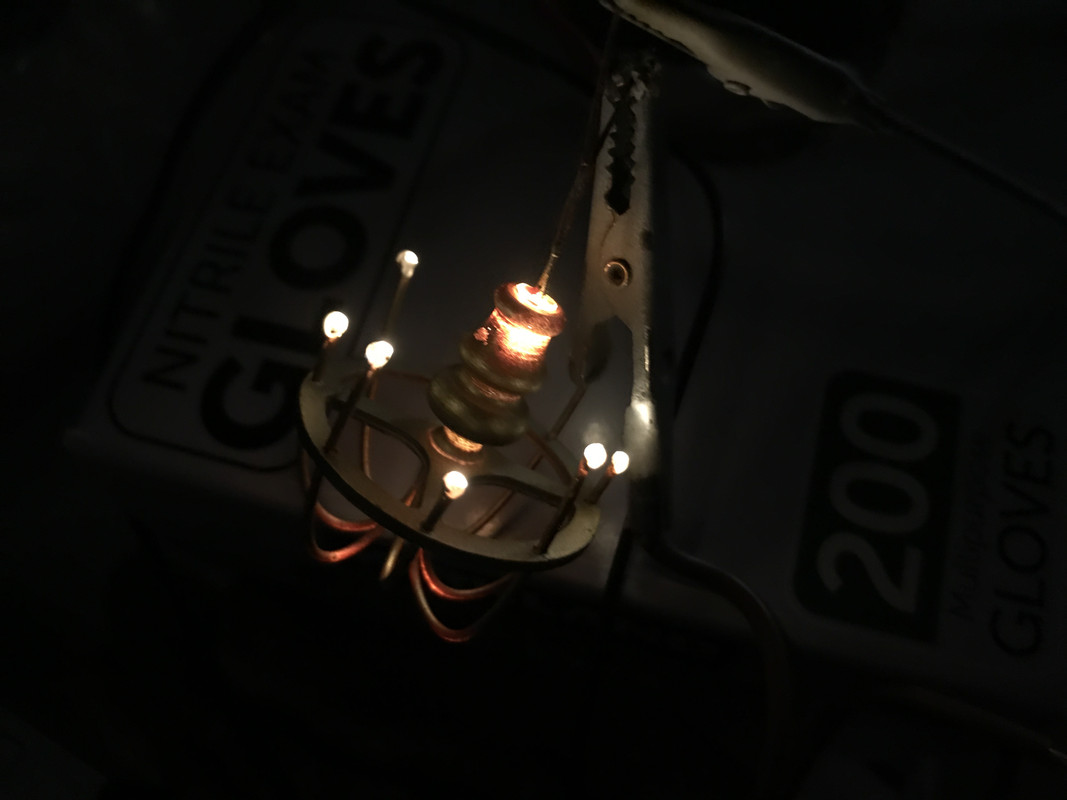

Resin printers work by creating an image of pixels representing a layer that needs to be created in the resin. The UV light cures this resin on an aluminum build plate. The exposure time varies with the layer thickness you’ve chosen and the type of resin you’re using. My exposure times are between 8 and 9 seconds per layer. Where the UV light illuminates the resin partially it hardens and then the build plate rises to break the seal between the last cured layer and the clear teflon film that seals the liquid resin vat from the LCD/UV light system that lies directly below. The build plate then returns one-layer-height above its previous location and the process starts over, only this time, the LCD projects the image of the next layer. This process repeats over and over again until the completed object rises out of the vat, like magic. The curing is partial so the next layer will stick and blend with the previous layer.

That was a very simplified explanation of what you need to know to make successful prints. There are many variables. The same is true for string printers. They are not fool proof. Resin printers are neither.

After the part is formed, you must wash it with 95% isopropyl alcohol to removed the layer of uncured resin that comes out of the vat with the part. You then have to cut off any supports (more about this later) and then fully cure the part in a UV chamber. Mine is a UV light array bought from Amazon mounted through the wall of a cardboard box lined with aluminum foil. I also bought a AC powered turntable to evenly illuminate the parts. I have the UV light and turntable powered through a digital timer. I generally post-cure parts for 15 minutes. Before I got the timer I over-cured some parts. They turn brown and get as brittle as glass.

Print Success Variables:

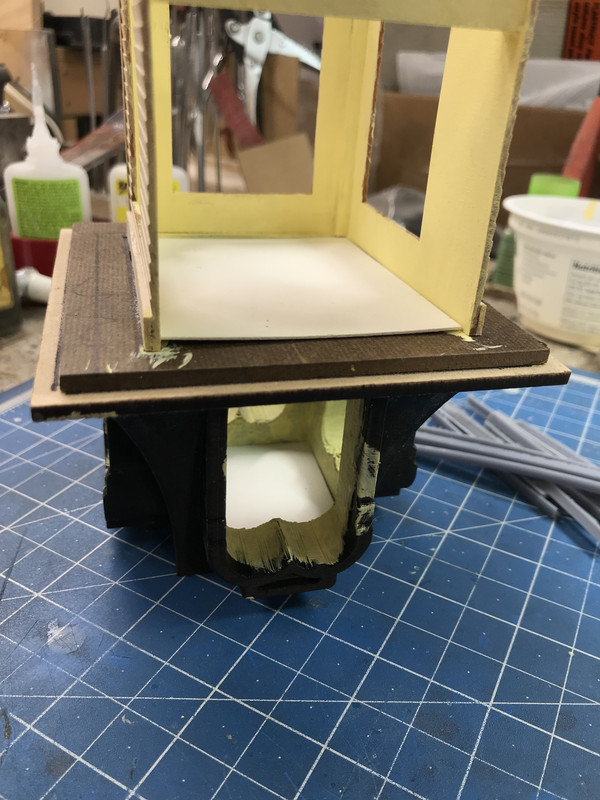

The first varialble are the first layers. These first layers must stick to the build plate, and stick hard. The most common failure is the object not connecting to the build plate at all or failing to adhere sometime later in the print. I was having problems with this and finally resorted to pre-coating the build plate with a thin layer of resin and curing it for about a minute in my UV curing box.

The build plate (z-Axis) must be able to pull the forming part off the teflon film so new resin can backfill into the vacated space to create the next layer. There is suction created between the formed part and the teflon. This suction can be very strong. When the suction exceeds the build plate adhesion the part will stick to the film and the print fails. When the part can’t be lifted the next layer doesn’t form since no new resin can displace the previous layer. It’s quite frustrating. One of the strategies is to print the part on an angle that minimizes the surface area contacting the teflon.

Resin printers have only one moving part and that’s good. It’s an optical process. The Z-Axis is driven by a stepper motor through a precision lead screw. I experiemented with different Teflon films to find the one that works best most of the time. The only mechanical adjustment is ensuring the build plate is parallel with the Teflon film. This is done by bringing the machine down to the base 0 position with the build plate set screws loosened. When the plate settles in, you lock the screws. That’s it! It’s so easy to set up, that you’re printing within 15 minutes of unpacking the box.

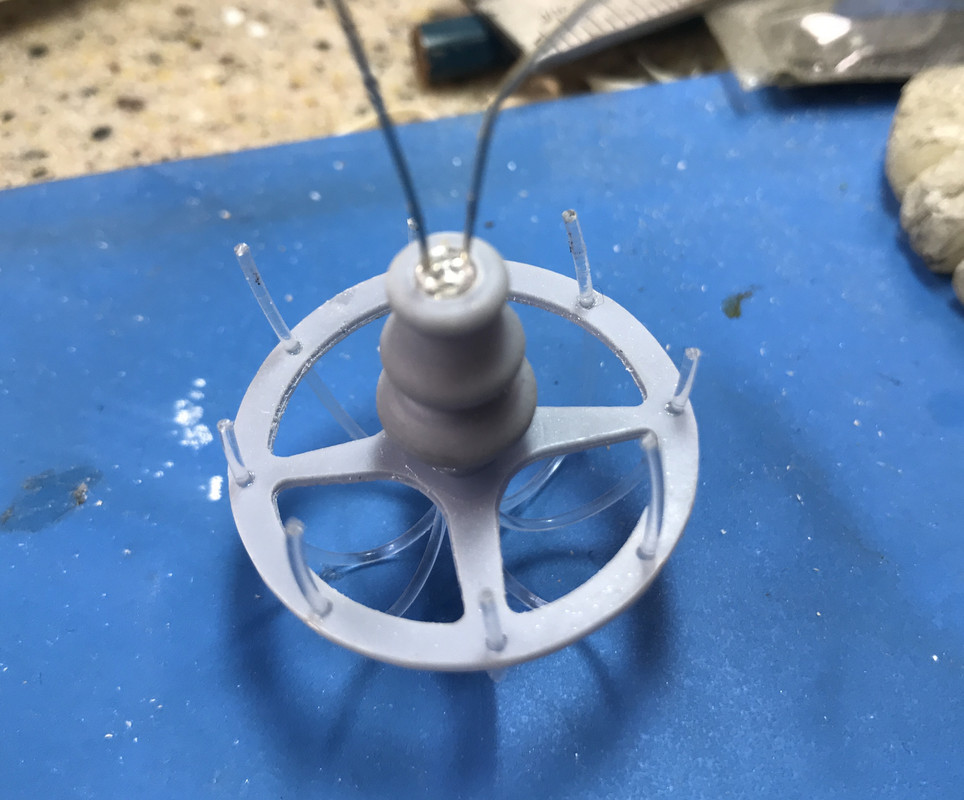

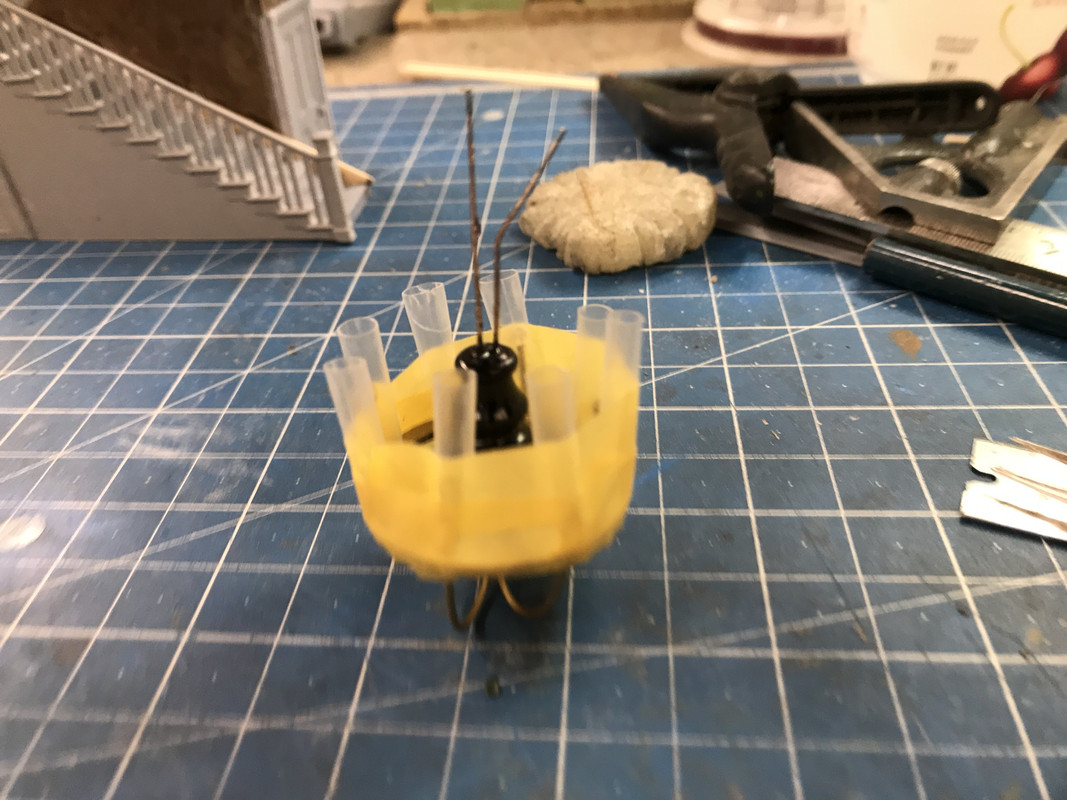

The other print variable is the support scheme. This is a bit arcane so bear with me. For an object to form every part of it must be anchored back to the build plate. It makes sense that if you can’t lift any previously cured resin off the teflon, the next layer can’t form. With simple objects having no overhangs, you just orient the object straight up on the build plate. But many complex parts have overhangs and edges that may start to form before the object connecting it to the whole has formed. These non-forming entities are called “islands”. There is software to help identify where they are.

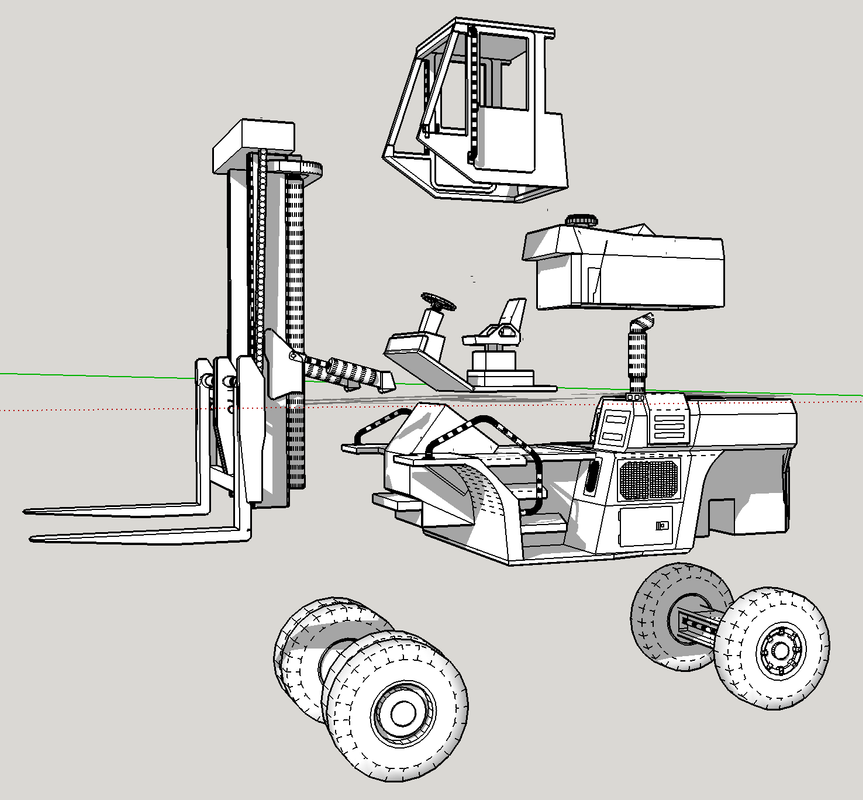

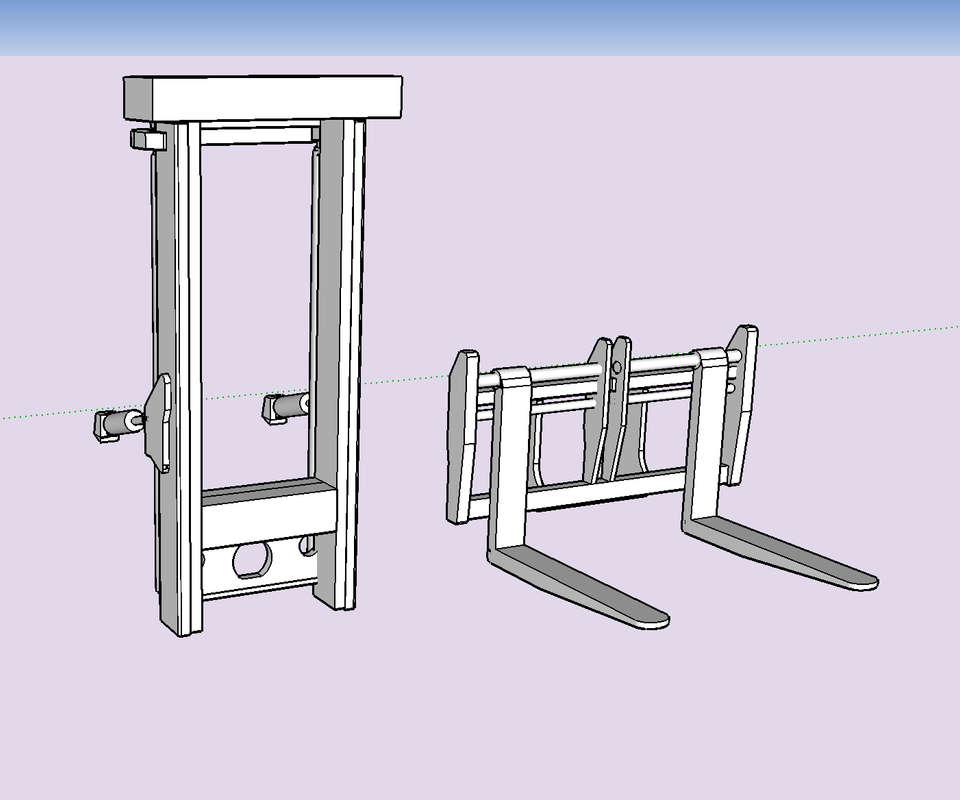

You draw the object in 3D drawing software. I used SketchUp. There’s a free version that’s cloud-based and an expensive pro-version. I’m using a client-based free version that Trimble stopped supporting three years ago. The 3D printers can’t interpret 3D drawing program output. They need to be converted. But that’s not all. These converted draw files need to be sliced. They need to be broken down into individual layers so the printer can create them. This is a two-step process. First the SketchUp drawing is converted to an STL file. This is a conversion program available for 3D software programs. There are two meanings for this acronym: Standard Translation File or Stereo Lithography File.

The STL File describe in explicit detail the outer surface of the object. For the STL file to render the object, the object must be a solid. This is a specific term used in 3D drawing. It means that if you filled the object with water, it would not leak out of any space. It means that all surfaces and edges are connected with no gaps. Any surface not connected is seen as invisible to the STL converter.

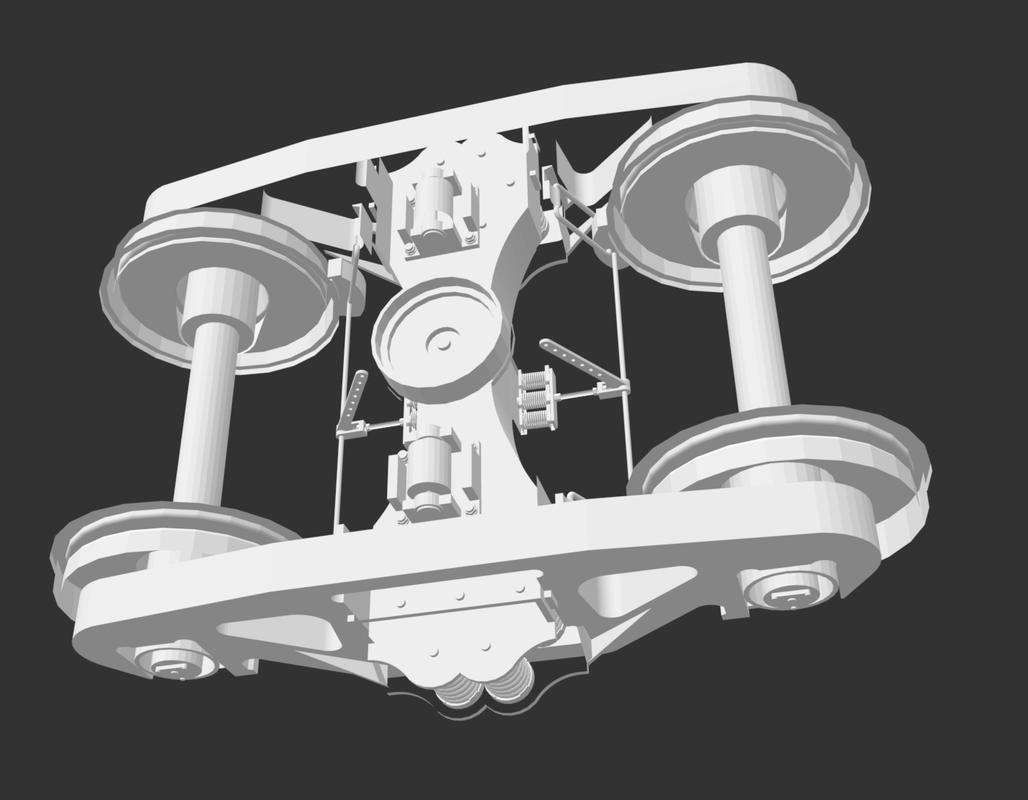

This is what the part looks like in the STL display. In this image you see that something’s wrong. It appears that surfaces are missing. As you’ll see, this is the result of non-normal facing surfaces present in the origianl SU drawing.

It gets worse. Not only must the object be “Solid”, but it must have all “normal facing surfaces”. This one trips up a lot of designers. In SketchUp you can draw a face with it’s outer surface facing outwards or it’s inner. The outer surface is considered “normal-facing”. You can push or pull an object while drawing it, and depending on which way, will create a shape with inside or outside faces on the outside. STL converters do not recognize wrongly facing surfaces. They are invisible. So there are two factors that make a 3D drawing unprintable. This is analagous to pulling on your socks one way and having the outside facing outwards, or pulling from the other way and having them inside out. Inside out faces DO NOT PRINT.

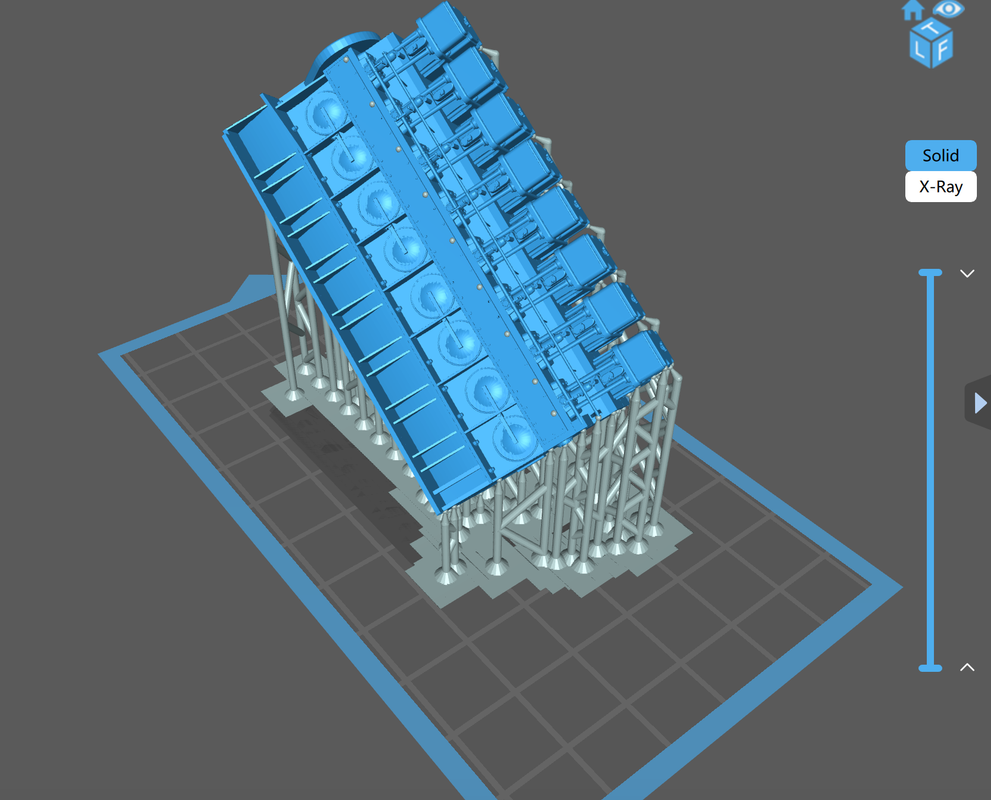

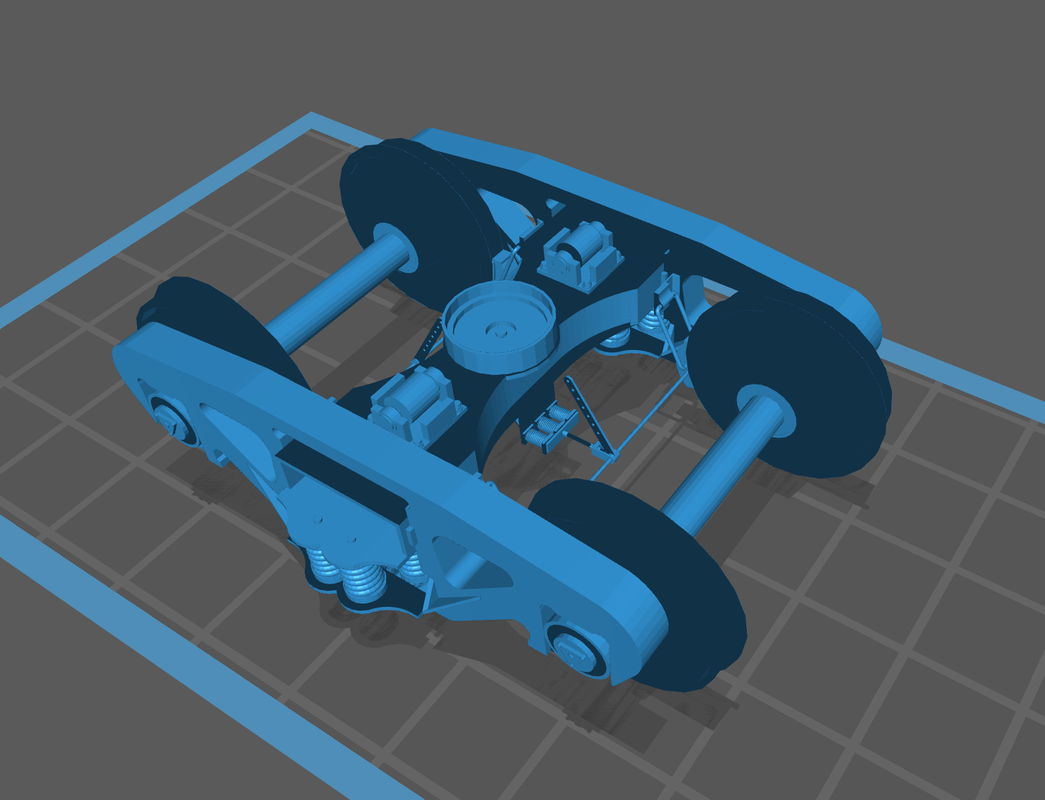

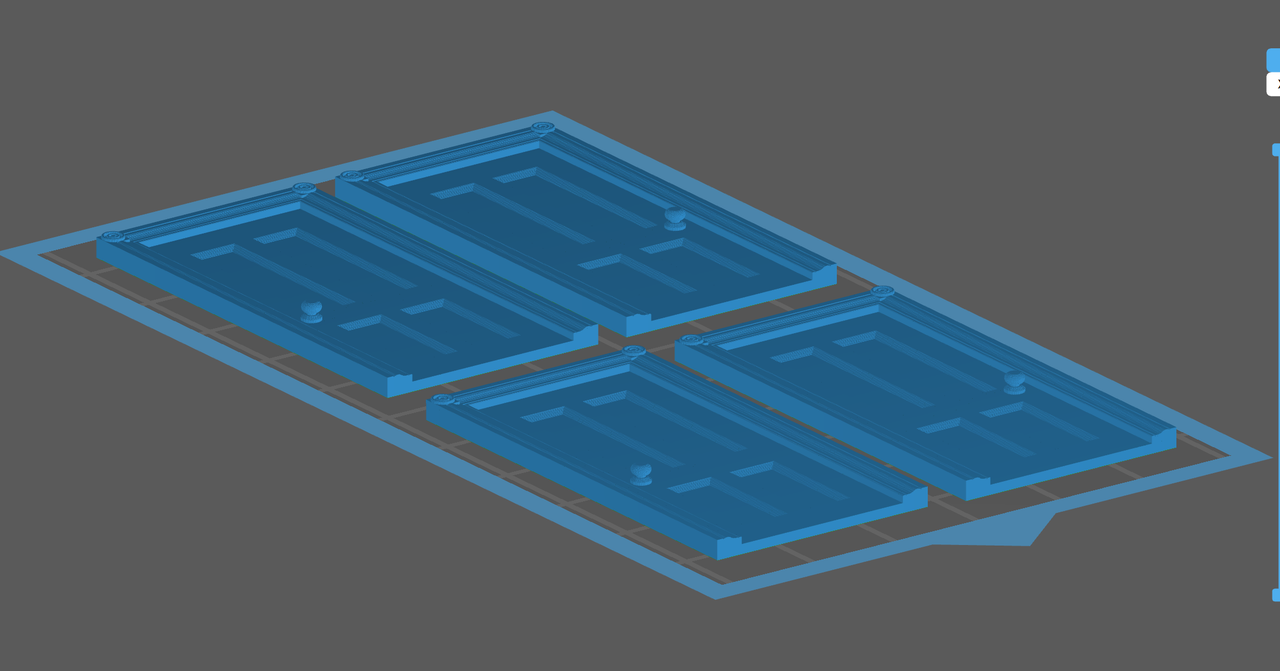

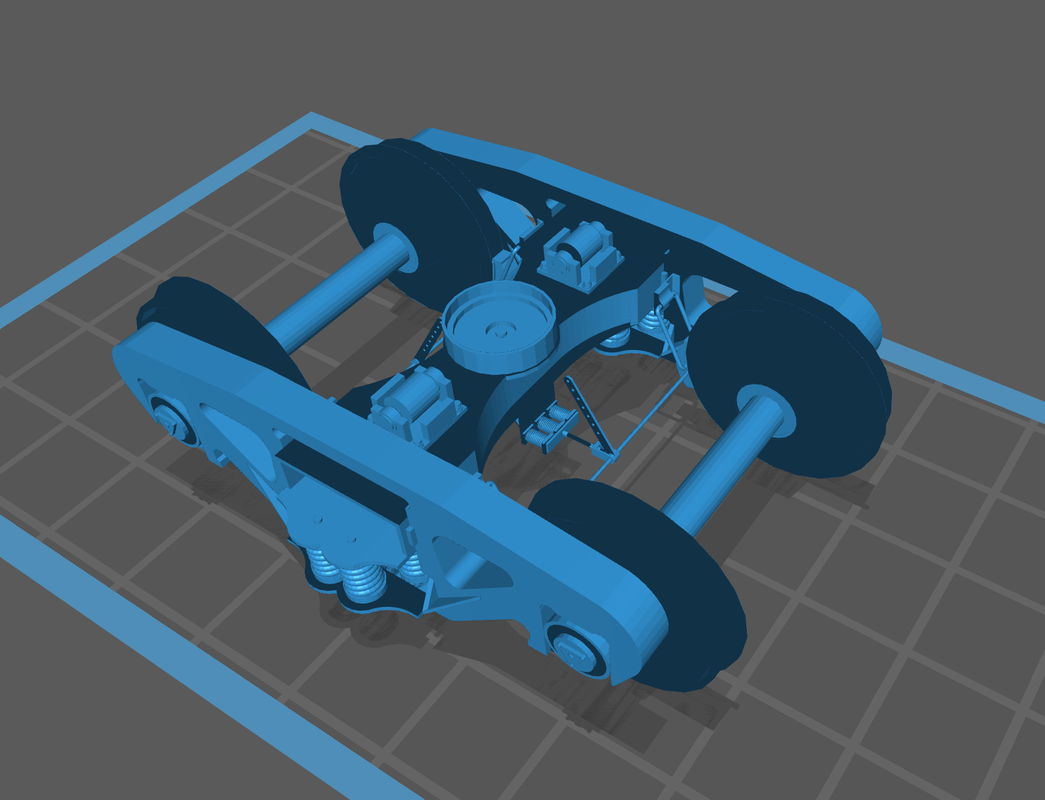

The slicer creates the actually machine file that commands the printer to generate each layer. The slicer shows images of the part as it will be when formed. You can manipulate this image to position it at angles and add supports where needed. It also shows any unprintable surfaces. They just image as black holes. You have to pay close attention to all these aspects to create successful objects.

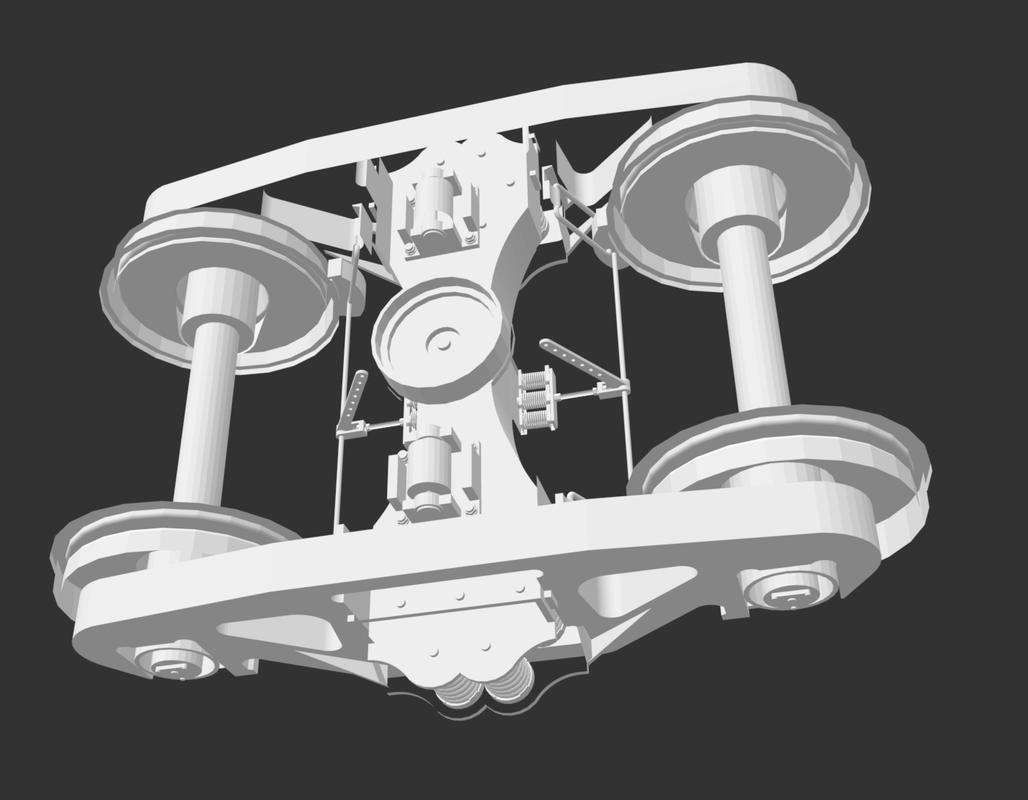

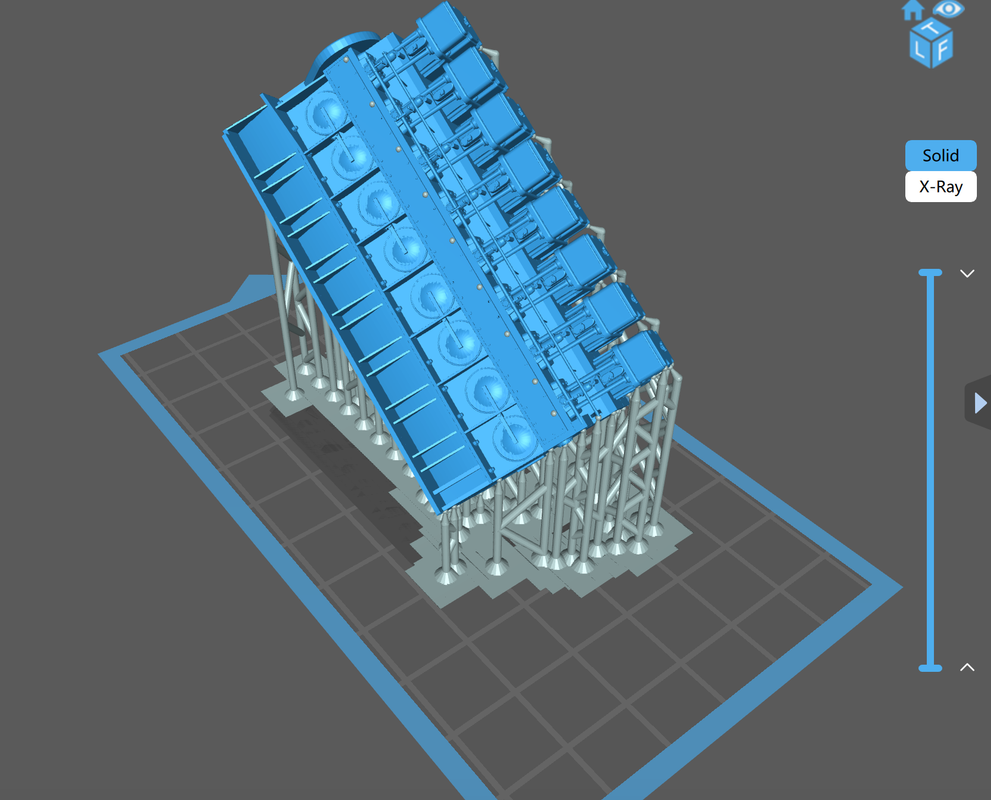

Here’s a screen print of what you see in the slicer display showing the forest of supports needed to successfully print the part. This is one half of a model locomotive diesel engine. The object is printed at an angle to reduce the contact footprint which helps to prevent the vacuum suction from pulling the object off the build plate. In the printer, it prints upside down so as the part forms in the resin it is being pulled upward. When printing highly detailed parts such as this half engine, I also have to spend a lot of time ensuring the supports aren’t attaching to any delicate details, like those pushrod tubes. Small details can be destroyed in the process of cutting off the supports.

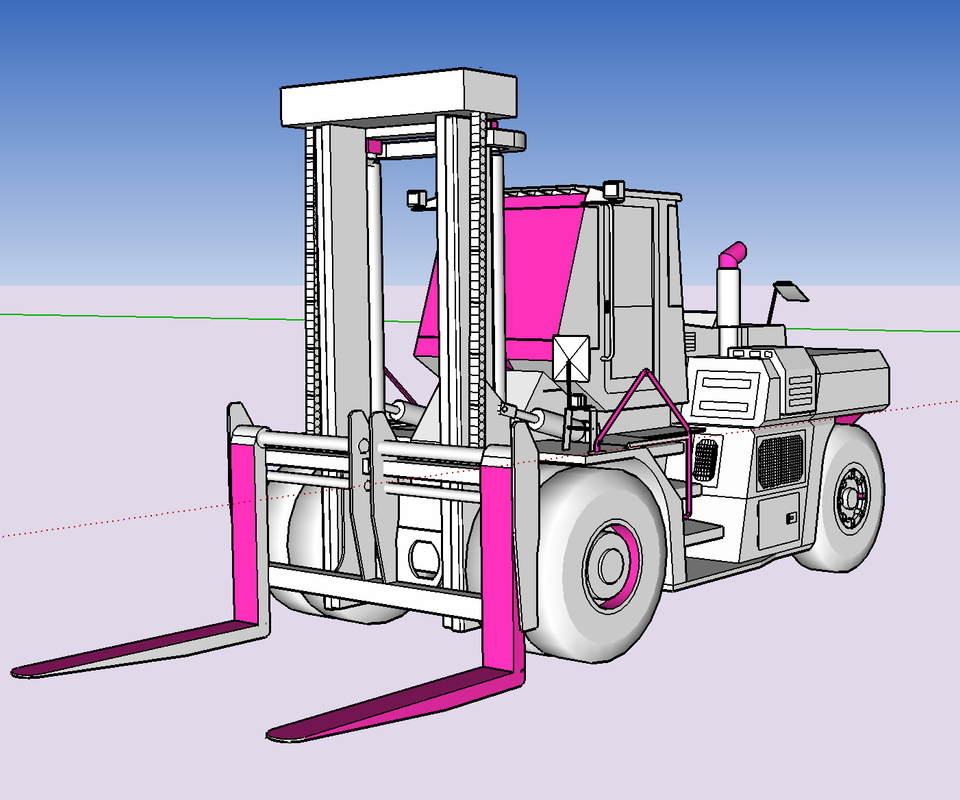

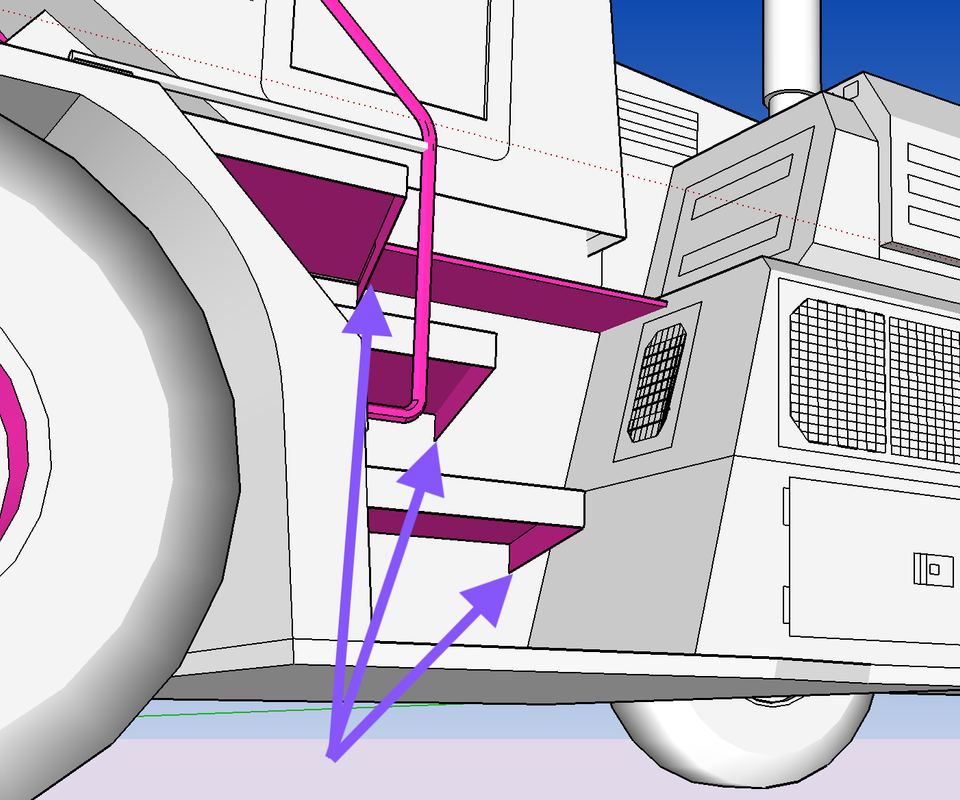

Many of the objects I create use drawings downloaded from the SketchUp 3D Warehouse. Some these drawings are gorgeous, but unprintable. The artists were drawing with the goal of creating a nice looking drawing, but weren’t concerned with 3D printing. When downloaded, I turn off the color and set SU to show any reversed faces in bright, hard-to-ignore, colors. I quickly find what editing needs to be done.

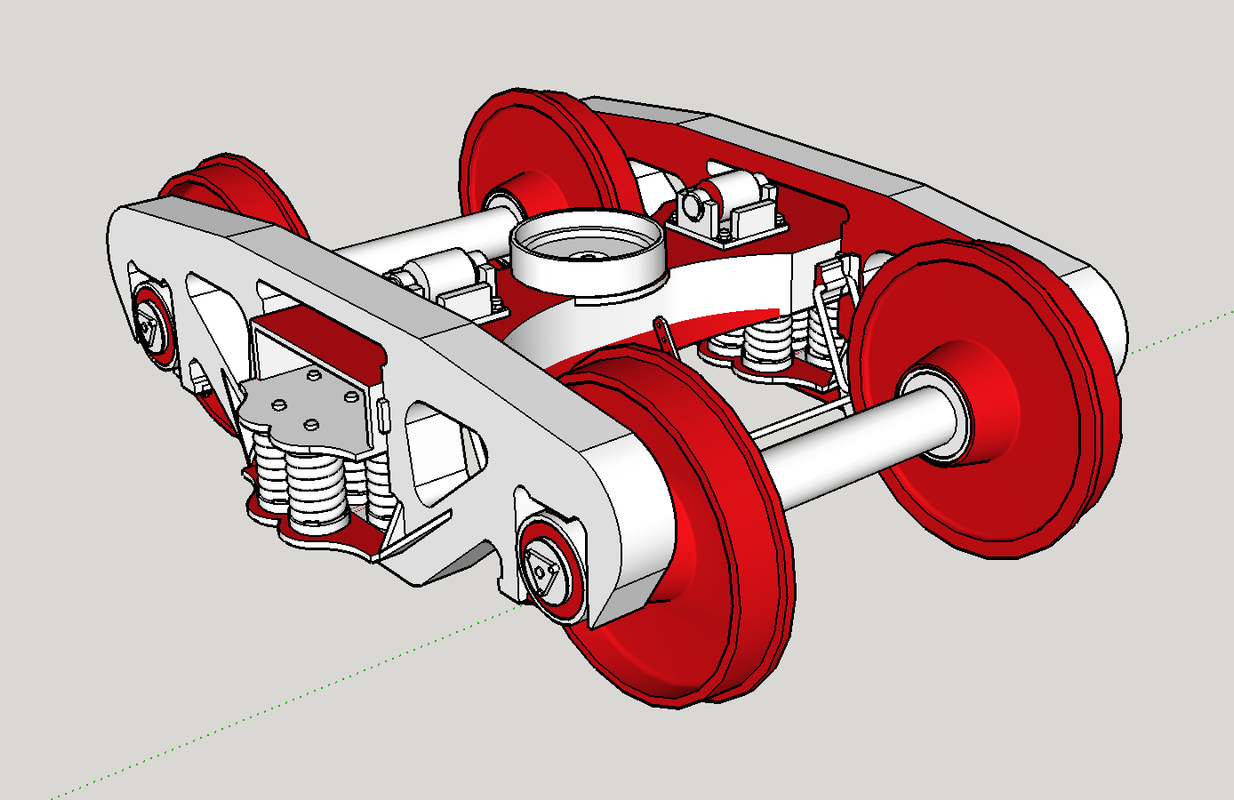

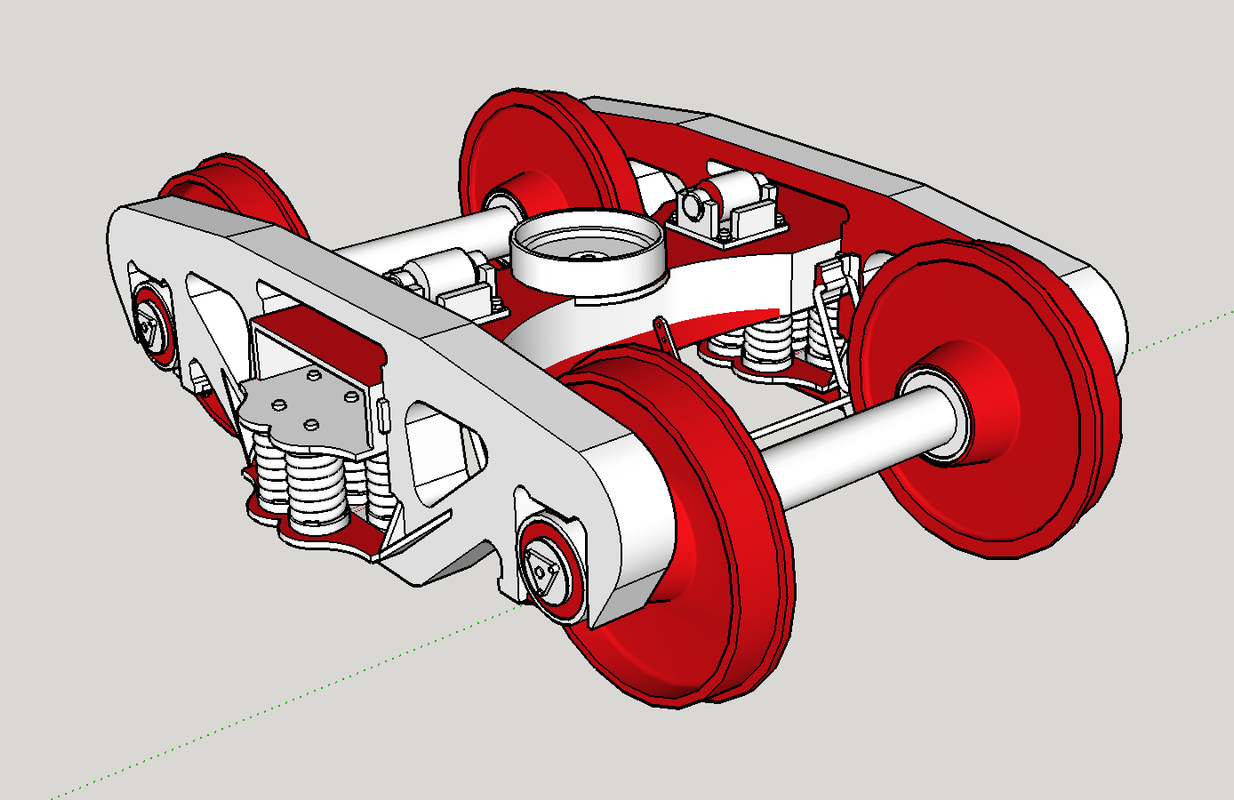

Everything in this drawing that’s bright red shows a reversed face. None of this would be seen in the STL converter and thusly, nothing would be seen in the slicer. I you refer back to that STL image you can see all these red faces showing up as invisible surfaces.

When a reversed face is brought into the slicer, the missing surface shows up as black. None of these black faces would print. I you put it in the machine it would look like something coming from a failed transporter transmission on Star Trek. It would just be a mess.

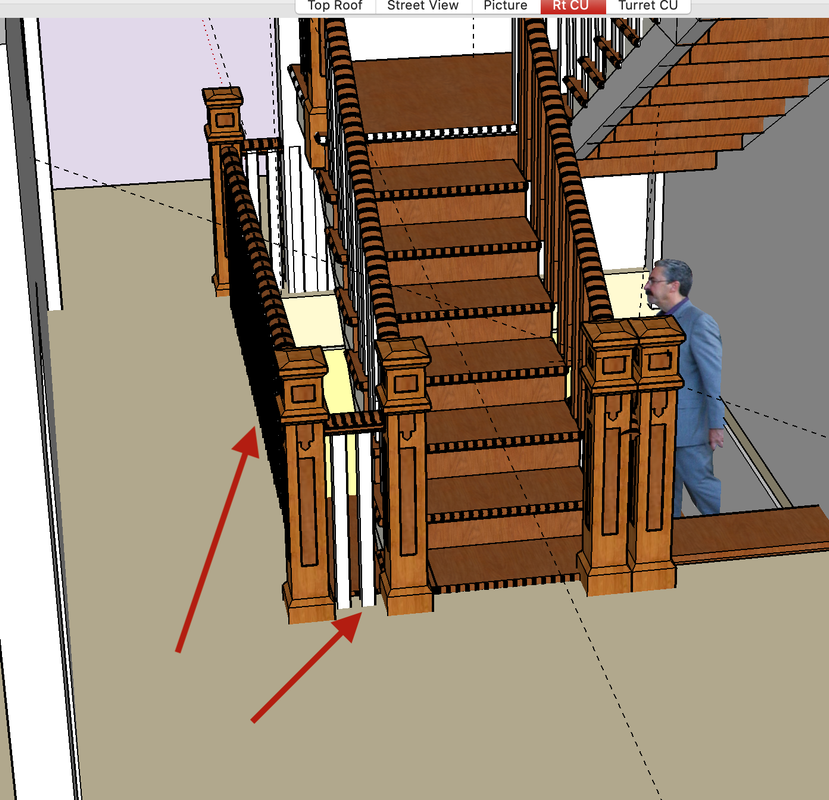

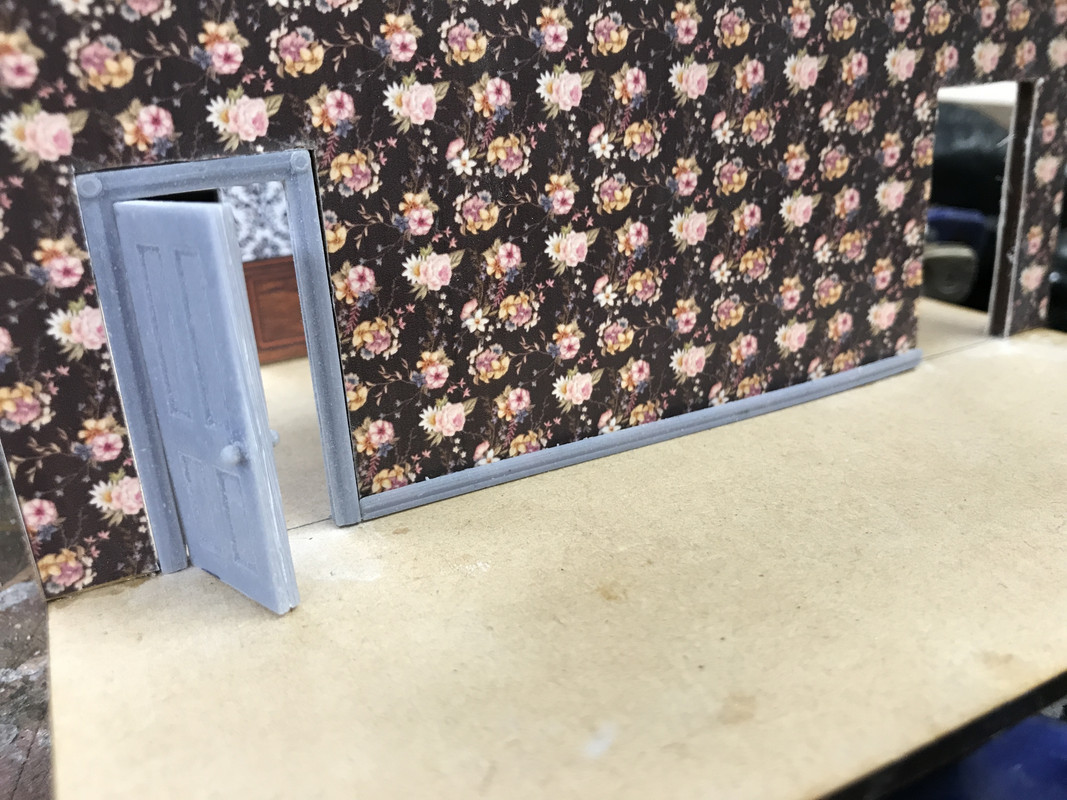

If you buy or download complete and tested STL files you don’t have to worry about any of this, but if you plan on developing your own images or download drawing from the SketchUp Warehouse, you need go be prepared to do some more work. That railroad truck with all the reverse faces was downloaded that way from SU. Some of the drawing take many hours of editing to prepare them for printing. This is what happened when I downloaded the basis for the elaborate staircase in the House.

While I could have custom-drawn an entire stair case, I always choose to download rather than draw from scratch if possible. It can save a lot of time. In the stair’s case, much had to be modified… almost everything.

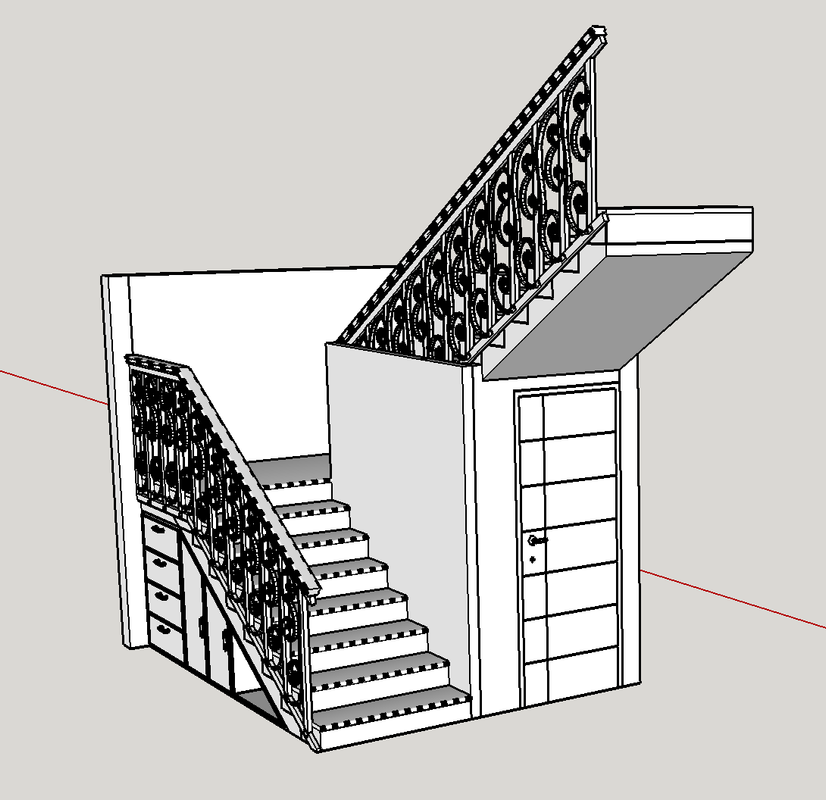

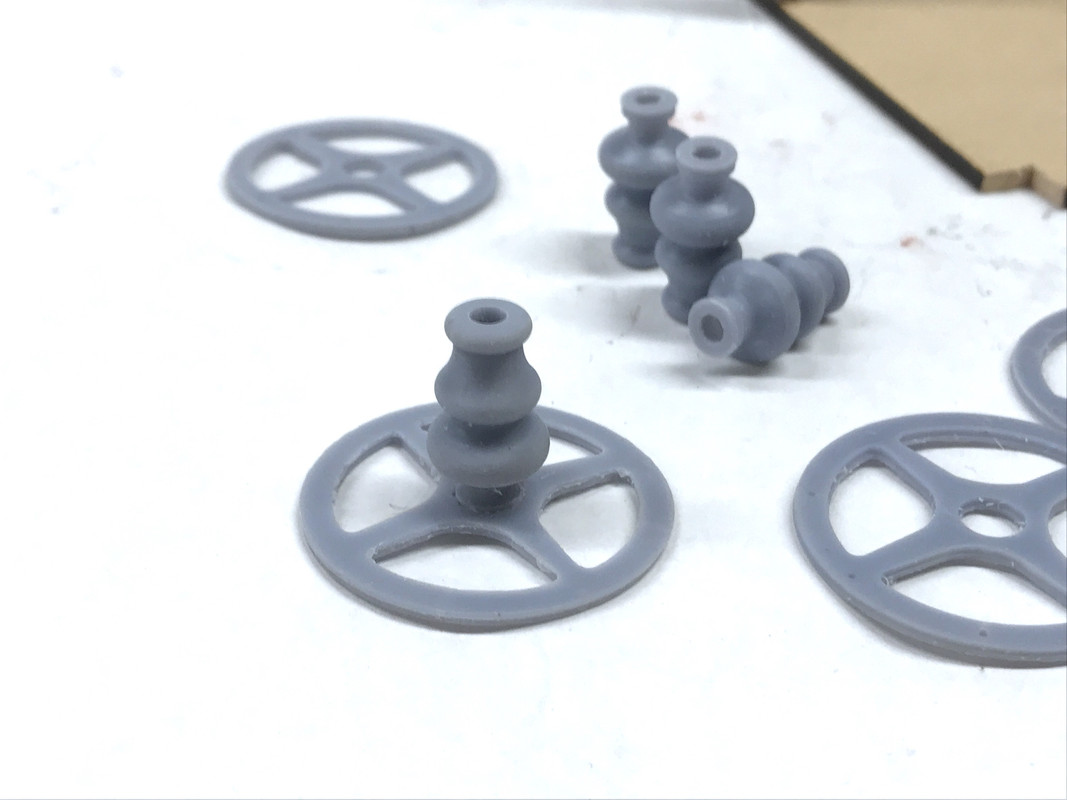

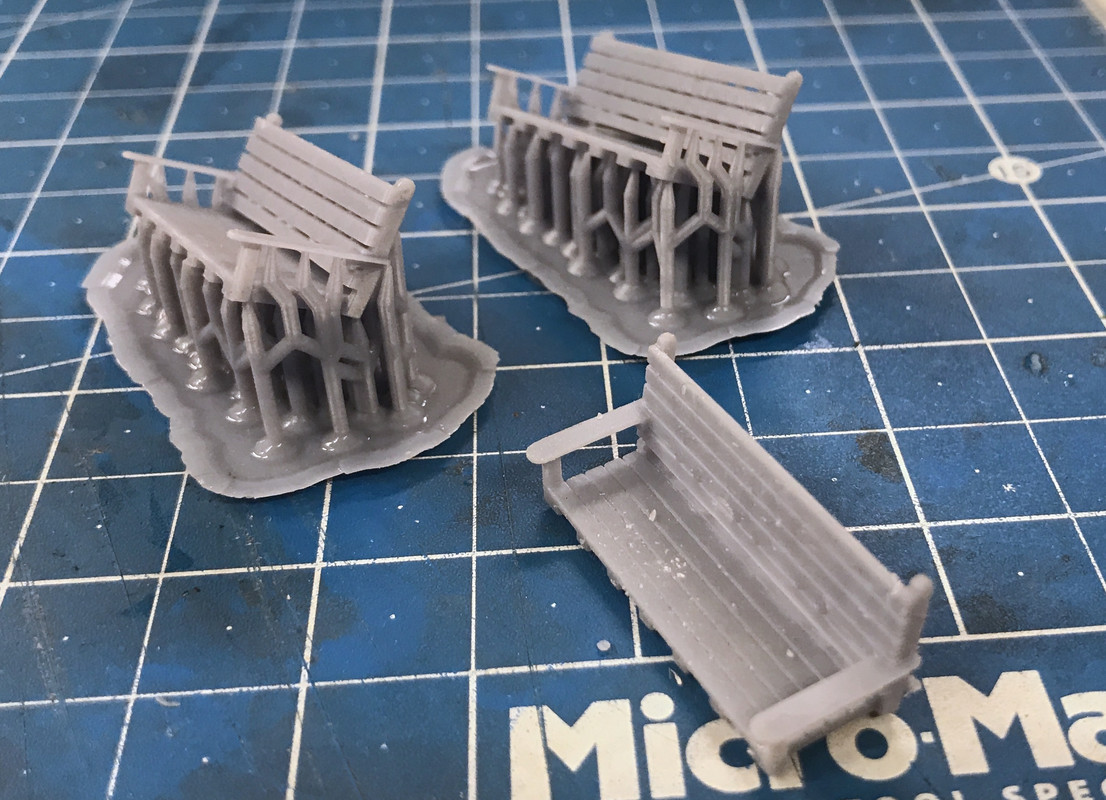

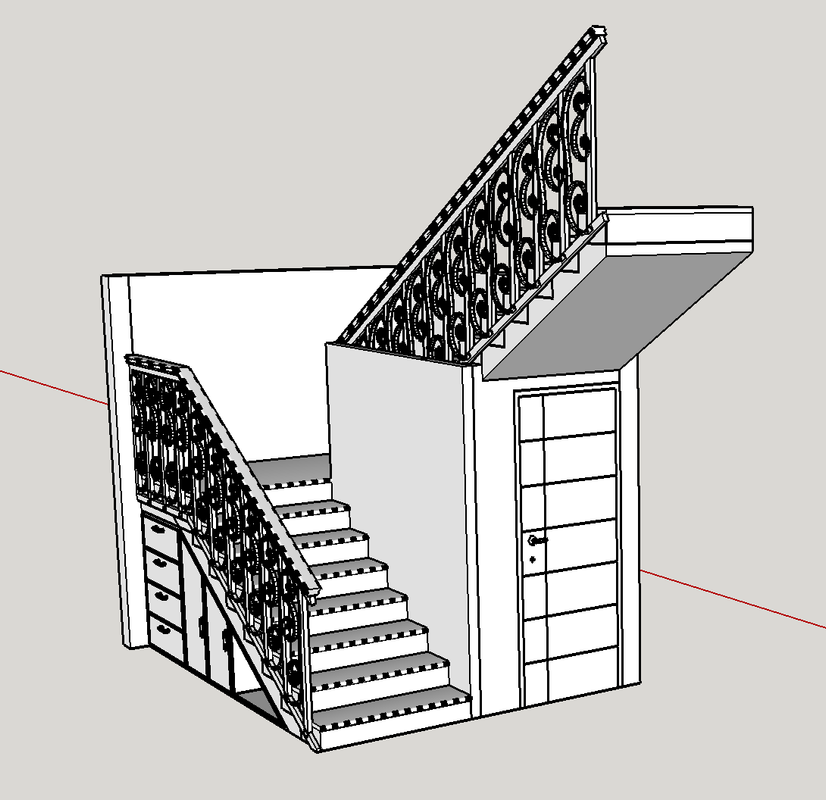

This is what I downloaded. At 1:48 there are some other considerations. Note: this screen capture was taken AFTER I had corrected all the reveresed faces. An unsupported surface much thinner than 3/64" ends up being too fragile to exist in the real world. So those wrought iron rail spindles, while very attractive, would be a disaster. The printer would attempt to resolve them, and probably could print something, but they would shred in trying to remove them from the build plate. I had to come up with another design.

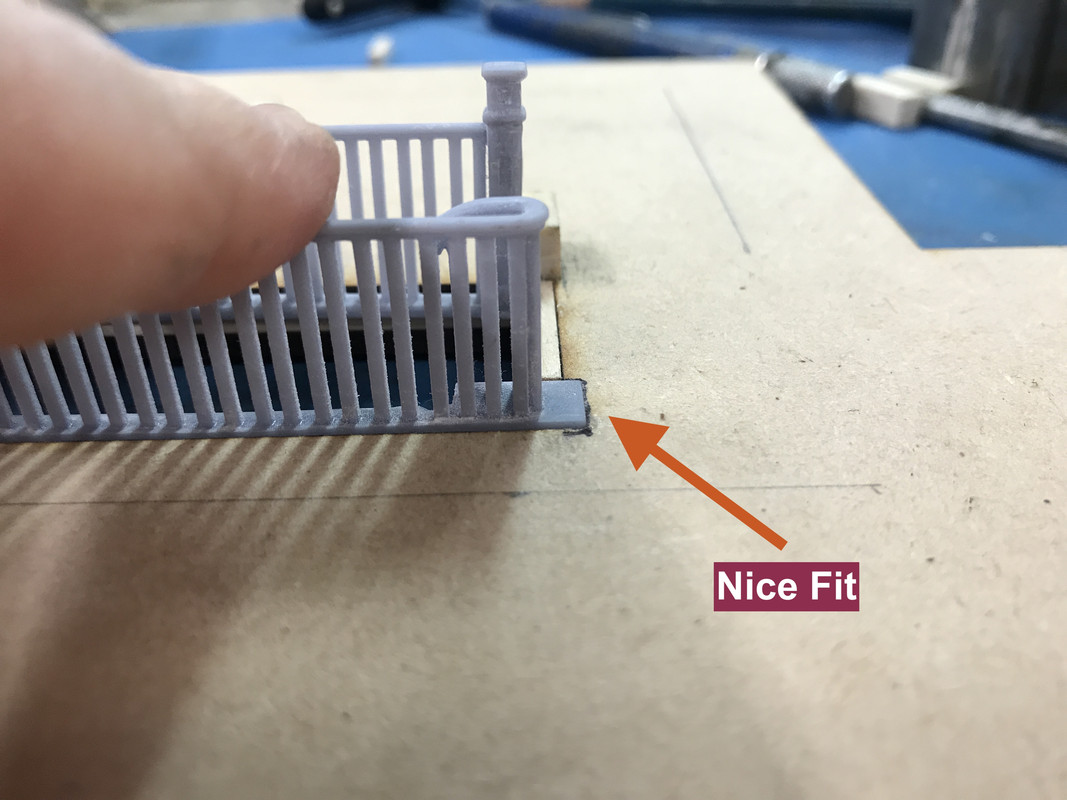

I went to a turned spindle and printed two attempts. The first was pretty scale (read that too thin) and they didn’t hold up at all. The second attempt was a little better, but wouldn’t produce a reliable job. I finally came up with a very plain square spindle that would be correct for a house of lesser opulance, but it would have to do. The difficulty arose where the spindle curves ended up created islands that required supports directly attached to them. While removing these supports a large number of spindles ended up destroyed.

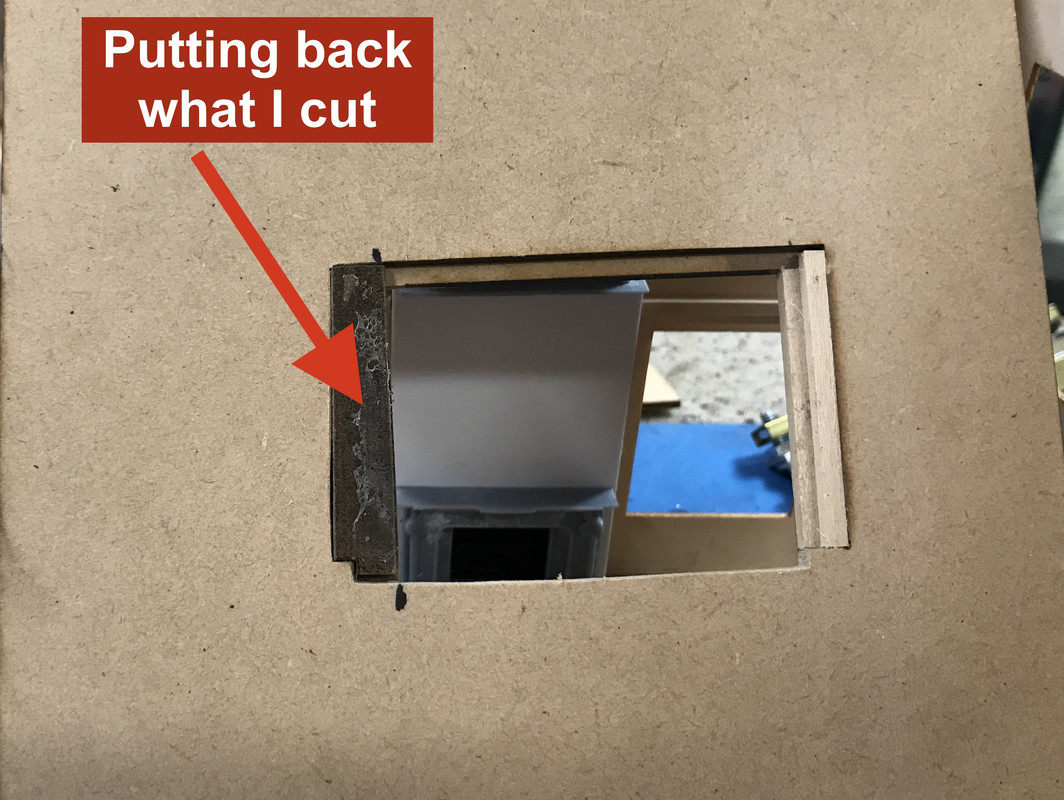

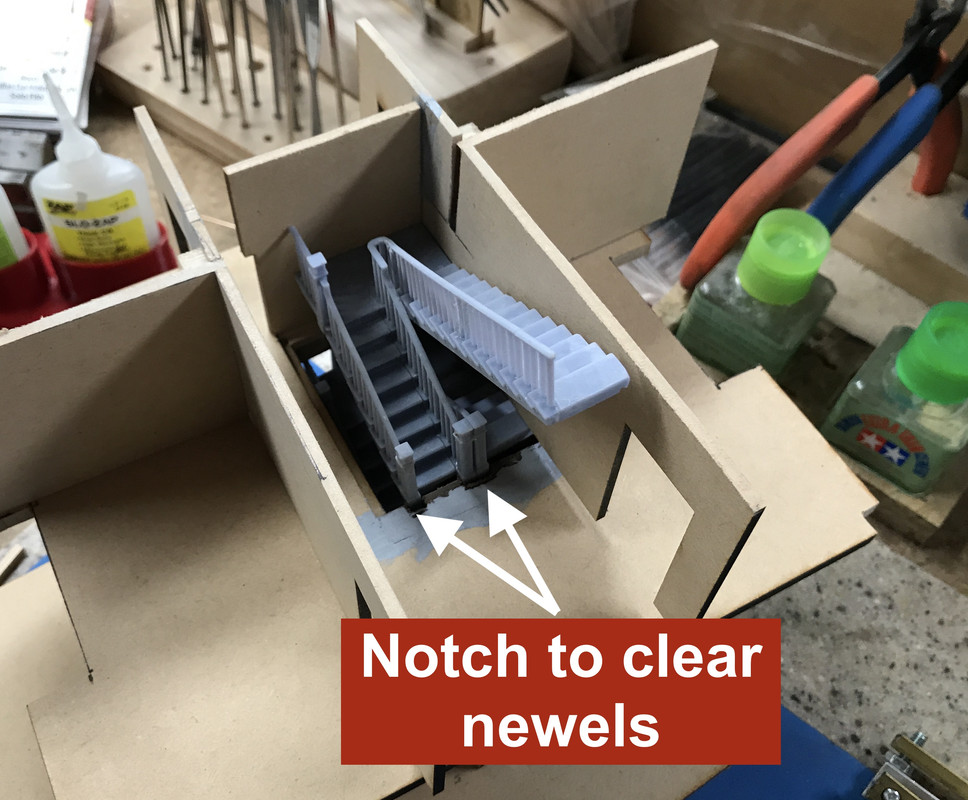

Then I needed to add another full flight, and develop turned railings at the inside turns, new newel posts, change the run lengths, and adjust the tread widths from the 2nd to 3rd story. In other words, I practically had to redraw the entire stair.

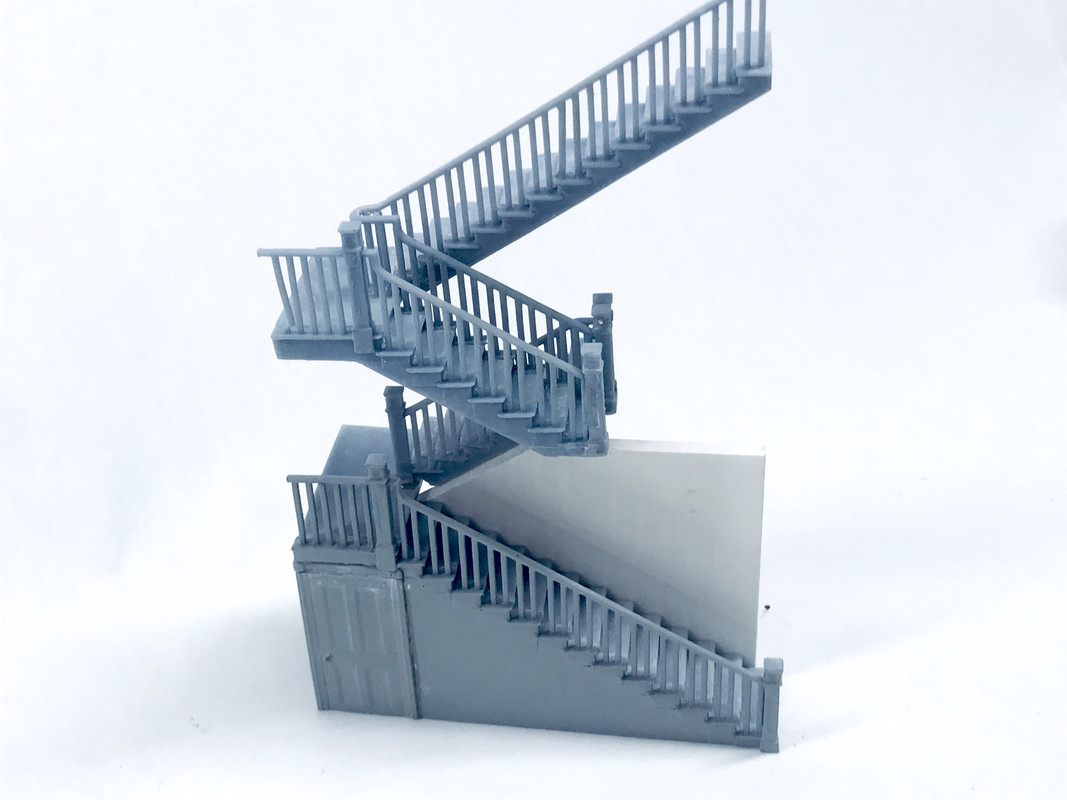

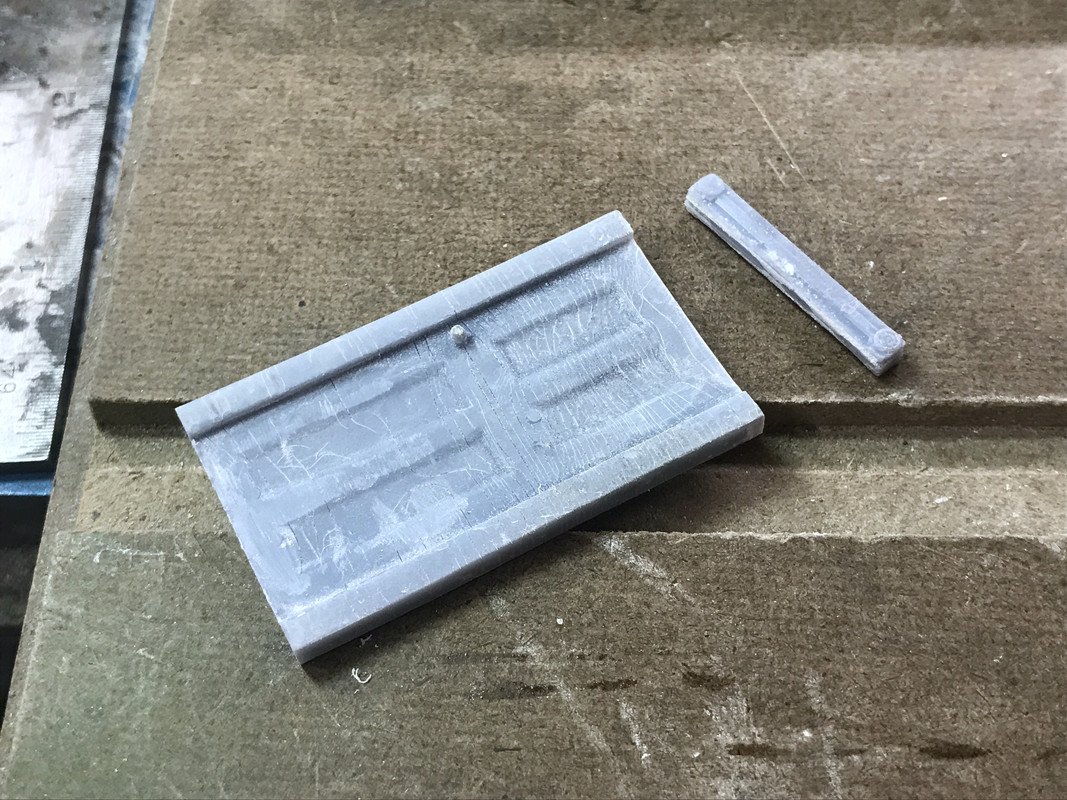

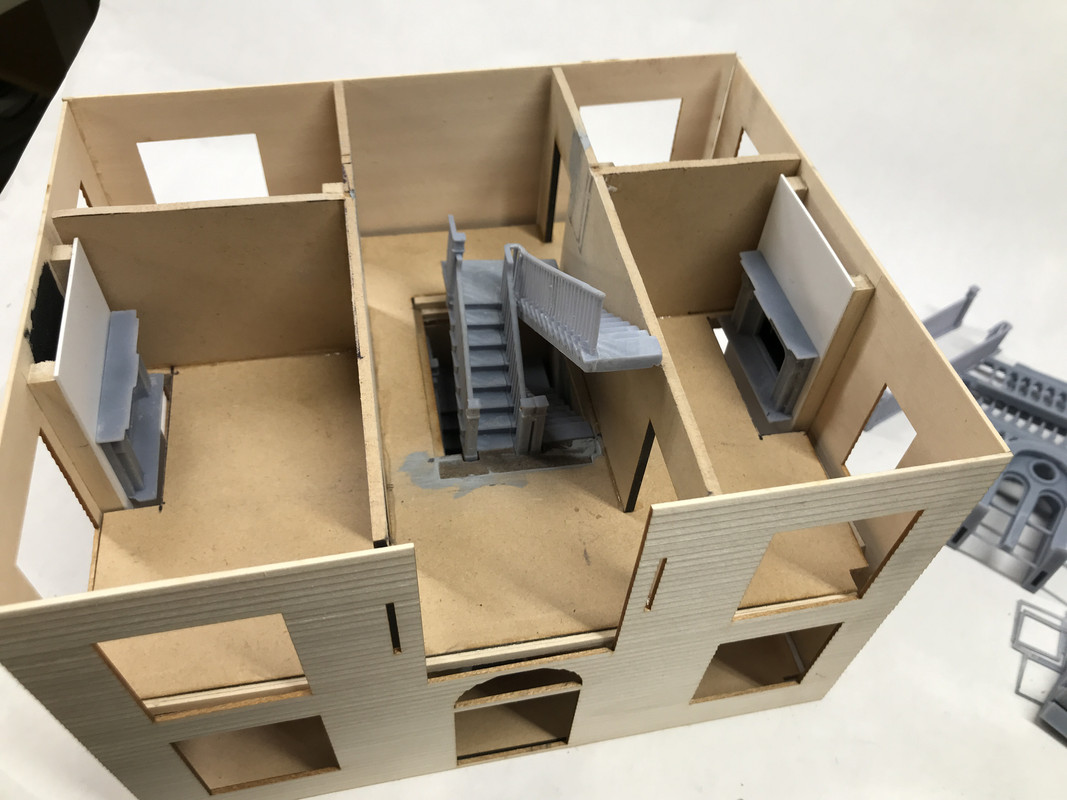

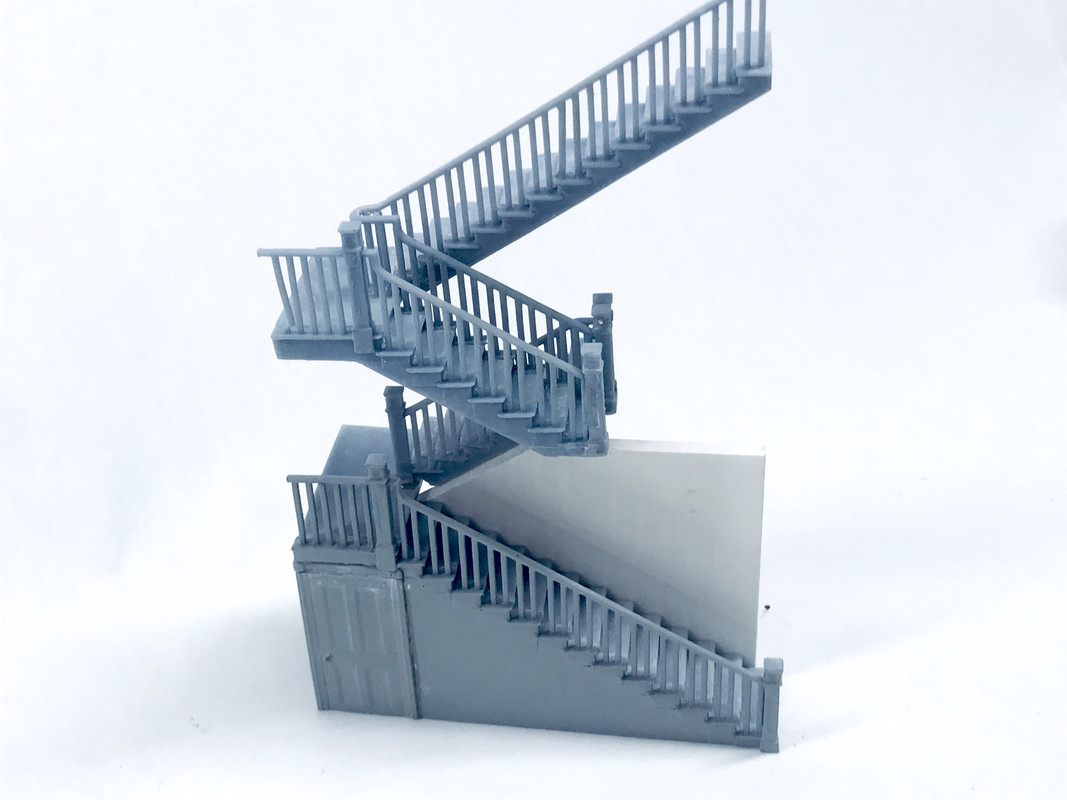

This is what I ended with. This print is 11 parts. In order to print the stair treads AND railing connected, I couldn’t print the entire stair. I required supports on the spindles. I ended up dividing the tread portion in two with a short section holding the spindles and railing, and the other making up the tread remainder. These were then glued together with CA. CA cures very quickly in the presence of the resin.

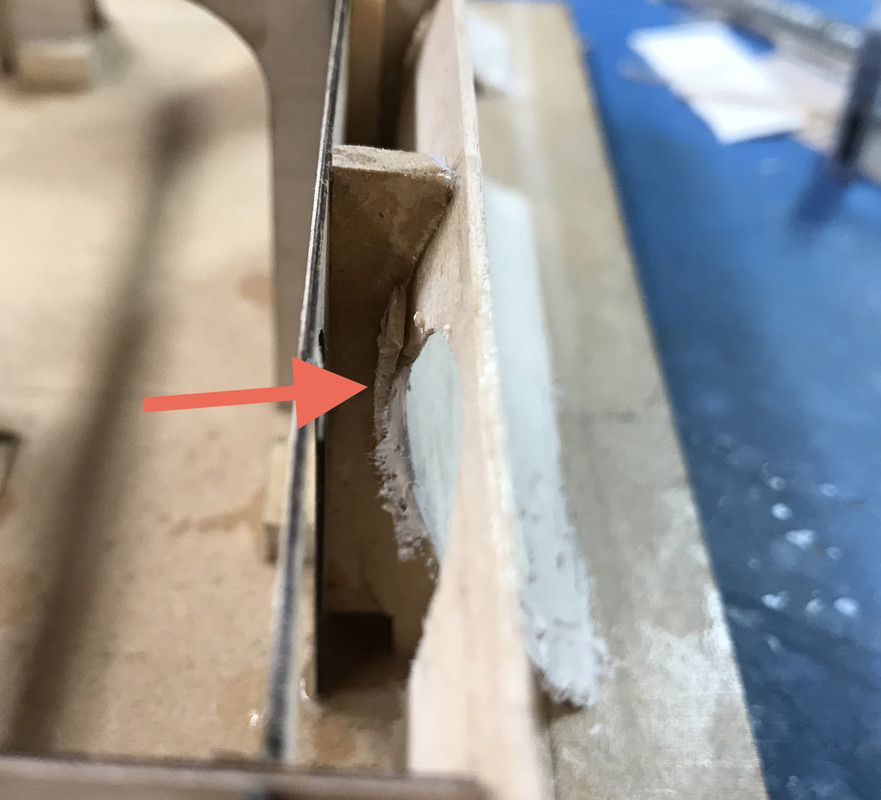

The other material used in finishing the prints is Bondic. Bondic is basically a higher viscosity version of the same UV resin of which the part is made. It can fill holes and join parts like welding and cures in five to ten seconds with the little UV LED that comes with it

This is a lot of information for the first post, so I’ll stop now and see who’s watching. The story will continue…